Misinformed Monitors: How Conspiracy Theories Surrounding “Ballot Mules” Led to Accusations of Voter Intimidation

Rumors around “ballot harvesting” have led to calls for members of the public to monitor ballot drop boxes around the country.

“Watch party” monitoring incidents, along with general concern around the practice, have led to larger worries over the potential for voter intimidation, primarily from left-leaning audiences.

This Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) analysis explores online conversation on Twitter and alt-platforms Truth Social and Telegram related to the monitoring of ballot drop boxes.

Our analysis highlights how a small number of influential accounts facilitated a participatory process with their audiences to spread false/misleading claims around ballot mules, as well as organize and/or support watch parties.

This Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) analysis was written by Stephen Prochaska, Kristen Engel, Taylor Agajanian, Joseph S. Schafer, Kayla Duskin, and Rachel E. Moran from the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public and Christopher Giles, Frances Schroeder, Ilari Papa, Emma Lurie, Mishaela Robison, and Michal Skreta from the Stanford Internet Observatory.

Introduction

Misleading and unsubstantiated claims around the use of ballot drop boxes have a long history. Around the 2020 election we saw repeated claims related to “ballot harvesting,” suggesting that ballot boxes were being used to drop off large numbers of illegally gained ballots. Since the 2020 election, the unsubstantiated claim that people were hired to drop fake ballots in boxes in swing states during the U.S. 2020 election to prevent Donald Trump from winning has become a prominent online conspiracy theory. The narrative was popularized in Dinesh D'Souza’s film 2000 Mules released in May 2022. Coinciding with the film’s release, the claims presented in it gained traction among online discussions and a fraction of reactions centered on demands for ballot drop boxes to be banned. A small contingency of the film’s viewers proposed monitoring or observing ballot drop boxes in future elections, but those posts did not initially gain much traction. However, our analysis signals a behavioral shift, showing how conservative actors have exploited the film and its claims to motivate members of online audiences to monitor drop boxes. For example, shortly after the initial (non-theatrical) release of 2000 Mules, a Twitter user posted a tweet saying:

2022-05-11 09:00:00 @[Anonymized]: Patriots need to put cameras around all drop boxes and post up and guard them. Personally greet the Mules at the Ballot Box. Let’s make them famous.

The above tweet was retweeted just over 2,300 times and echoes themes visible throughout the time periods we analyzed (specified below) – namely the conspiracy theory that “ballot mules” are a major avenue for election fraud, and that in order to stop them “patriots” need to protect the integrity of drop boxes so they can’t be used to cheat.

Recently, people associated with organizations such as True the Vote and Clean Elections USA are encouraging people to gather at drop boxes to monitor and film the dispatch of ballots, known as “watch parties.” They hope to document so-called “mules” attempting to rig the election.

Screenshot of the homepage for Clean Elections USA, one of the organizations which is attempting to organize ballot box watch parties based off of unsubstantiated rumors of illegal ballots being dropped into ballot dropboxes.

These organizations are linking the conspiracy theories presented in 2000 Mules to a specific call to action, for people to get involved in the prevention of alleged fraud and ballot harvesting. This is being framed as a “patriotic duty,” for audiences to personally engage in the protection of the election from these perceived threats.

The EIP has previously written about how documentation by the public, usually in the form of cell-phone recorded videos and images, is used as “evidence” of election fraud, despite lacking vital context and often showing blurred and unclear situations. This alleged “evidence” then functions to motivate both further searching for evidence, as well as mobilization to prevent alleged cheating — including monitoring drop boxes to prevent “ballot trafficking” (visible in our analysis here) or voting in person so post office workers don’t discard Republican votes (another prominent conspiracy theory).

The mobilization of drop box watchers has raised concerns that voters might experience intimidation from such activists, or that a perception of the potential for intimidation may have a chilling effect on voters dropping off ballots at dropboxes. A number of mainstream news outlets such as CNN and The Washington Post have reported about alleged voter intimidation, amplifying concerns from local election officials.

Background

The monitoring of election processes has a long history in the U.S. and is built into current practices. Sanctioned poll watchers are a long-standing component of US elections. Their role involves monitoring election administration at polling locations and reporting issues to polling authorities and party officials. Beyond this narrow observatory role, poll watchers are not meant to interfere in the process of voting. Poll watchers are also known as “partisan citizen observers” as they represent a party in the enactment of their role. States have different rules on who can be a poll watcher, and some have limits on the number of poll watchers at various polling stations. Furthermore, official poll watchers are located at polling stations and at vote tabulation centers. In contrast, mail-in or absentee ballot drop boxes do not have official procedures in place for whether poll watching is allowed and what poll watching should look like in these contexts.

This gap in policy has created fertile ground for conspiracy theorizing, where audiences already primed to see “evidence” of election fraud interpret the lack of established practices as having a strong potential for abuse. This perceived vulnerability was the focal point for D’Souza’s 2000 Mules, in which he and his collaborators presented widely discredited “evidence” that drop boxes were a major vector for fraud.

Since the release of 2000 Mules, a network of volunteer Trump-supporting groups have been conducting their own operations to monitor polling stations and drop boxes. These groups have put out calls for action, and have asked volunteers to film “suspicious” activity, seeking further “evidence” of fraud at the same time as rallying supporters to participate in activity that, in many cases, has been seen as voter intimidation.

The analysis below explores conversation around ballot box observation at two points in recent history, contextualized within conversations that surrounded the release of the 2,000 Mules documentary. We analyzed two separate time periods, Time Period 1: the primary election in Arizona where claims of ballot box observers were prominent, and Time Period 2: recent incidents, also from Arizona, highlighting concerns of voter intimidation attached to ballot box observation. We examine how unsubstantiated claims related to ballot harvesting have resulted in calls for members of the public to observe ballot boxes and how, in turn, the presence of, or potential for, “watch parties” has stoked concerns of voter intimidation that have been centered in mainstream media coverage.

A post on Truth Social on October 22 encouraging users to watch ballot boxes.

Data and Methods

To better understand the discourse surrounding ballot box watching, its role in accusations of voter intimidation, and connections to mis- and disinformation, we used a mixed-methods approach rooted in grounded theory to assess how the conversation has grown and spread over time, as well as how online discourse has contributed to the mobilization of “drop box watchers.” Grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014) involves iterative qualitative analysis during data collection and analysis in order to facilitate the construction and testing of hypotheses and theories rooted within the data being examined. The work discussed in this post is similar to previous research in crisis informatics (Palen & Anderson, 2016) as well as the study of rumoring (Maddock et al., 2015) and disinformation (Starbird et al., 2019).

We analyzed discourse on Twitter surrounding various incidents within two specific time periods between the Arizona primary and the lead-up to the midterm elections. Tweets for Time Period 1 were collected between 07/14/2022 and 08/06/2022 using keyword queries related to drop box watching and ballot harvesting, refined to reduce noise within the dataset and resulted in a total of 18,674 tweets. A similar process was used for Time Period 2 between 10/18/2022 and 11/01/2022, and the resulting dataset comprises 190,761 tweets.

Following the creation of the dataset, we generated temporal and network graphs to chronologically map each incident and understand spread. Qualitative thematic coding of the 100 most retweeted tweets in each dataset was conducted to understand patterns and themes, resulting in the categories present in Figures 1 and 2 below. Finally, top domains were extracted to assess influential organizations and actors throughout the discourse over time. It is important to note that all accounts with a following under 100,000 (unless they are a public figure such as a political candidate) have been anonymized within this research output to protect user privacy. This process includes editing the end of time string to zero and changing some words of tweets to make searching more difficult while retaining tweet meaning.

In addition to our analysis of conversations on Twitter, we also examined discourse as it existed on Truth Social and Telegram, identifying key influencers and the spread of related rhetoric and conspiracy theories. Due to data access and platform affordance limitations, quantitative analysis is difficult on these platforms, so our analysis relied on identifying influential users and posts (based on metrics such as number of views) to better understand the drivers of conversations.

Time Period 1: Primary Election

Preceding the Arizona primary on August 2, various right-leaning groups shared a call-to-action with Arizona constituents imploring them to physically surveil ballot dropboxes through camping out and capturing photo and video evidence of voters as they drop off their ballots. Though some voters did turn out to watch ballot boxes, the Arizona primary ran smoothly with only minor issues arising with in-person voting (rather than ballot drop-offs) due to a ballot shortage at multiple voting locations in Pinal County.

Prominent accounts and domains

The Twitter conversation surrounding monitoring drop boxes during Time Period 1 primarily consisted of positive support for watching drop boxes. We identified 18,674 tweets related to monitoring drop boxes, of which 76.5% of these tweets were retweets and 8.4% were quote tweets, and 17.1% included links to external domains. The most tweeted domains are summarized in Table 1 below, consisting of links related to elections in Wisconsin, Arizona, and Michigan. The top shared domain was the campaign website for Arizona House of Representatives and “America First” candidate Christian Lamar, which detailed a platform focused on revising election law and decertifying “bad faith” elections. This domain was linked more than twice as often as the other top domains. The Associated Press article which was the next highest-shared domain debunked the claim that ballot boxes led to fraud in the 2020 election, to include contextualizing the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruling outlawing ballot boxes (the third-most shared domain) and the unsubstantiated film 2000 Mules. Tweets linking to the talkingpointsmemo.com were of an article titled “Trump And Co. Seize On Wisconsin Ruling As PROOF 2020 Election Was Rigged,” which debunked claims that ballot boxes were used as a vehicle for fraud and summarized reactions by right-wing influencers to the court case. Other top shared links include a since-removed YouTube video, official Maricopa County information on drop box and voting locations, a Facebook Watch live stream hosted by 100 Percent Fed Up with The Gateway Pundit about alleged election fraud in Michigan, reporting on an “Election Security Forum” in Arizona where Republicans encouraged drop box monitoring and data collection ahead of the primary, and several articles from The Seattle Times and The Gateway Pundit.

The spread of related conversation on Twitter during this time period was limited, and was dominated by a small number of tweets from high profile accounts. The most spread tweets were from Arizona Gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake (3,420 retweets) and conservative influencer @leslibless (an account that goes by “ProudArmyBrat,” 3,742 retweets). Right-wing political commentator Dinesh D’Souza also appeared in our dataset, primarily sowing doubt about drop boxes and ensuring the conversation continued to revolve around theories promoted in 2000 Mules. Influential accounts like @KariLake and @leslibless made posts that exemplify the most common frames. The first frame reinforces a suspicious, adversarial view of drop boxes where monitoring is framed as a necessary act to prevent fraud (extending the tone of 2000 Mules). For example, Kari Lake’s tweet below specifically references watching boxes in order to warn “potential mules” away from the box:

In a similar vein, a small number of tweets reinforced perceptions of Democrats (the assumed ballot mules in most iterations of these conspiracy theories) as deviously trying to fool patriotic watchers, e.g.:

2022-08-02 11:11:26 @[Suspended account]: 🚨💥ATTENTION ALL💥🚨

DEMOCRATS ARE USING MOBILE VOTING NOW SINCE THEY KNOW WE ARE WATCHING DROP BOXES THEY NOW USE VANS TO DRIVE THROUGH COMMUNITIES TO GET ILLEGAL BALLOTS SPREAD THIS LIKE WILD FIRE!

The above tweet was retweeted 203 times and, while the spread of rumors surrounding “mobile voting vans” was relatively limited in our dataset, the underlying tone implying that Democrats were trying to fool conservative groups was present throughout our data.

The second frame is directed at in-group members, and has a lighter more supportive tone that discusses the monitoring as “watch parties” or “tailgating,” often combined with pictures of people smiling or having fun. For example, @leslibless’s tweet amplified a picture of a group of people smiling while sitting in camping chairs in a parking lot, accompanied by language supporting their choice:

2022-08-01 00:55:36 @leslibless: Ahead of Arizona’s Tuesday Primary, residents are determined to safeguard the drop boxes, by having party “watches.”

This is how it’s done! Good for them!

Instead of focusing on demonizing the out-group, the tweet functions to build community and create positive sentiment for drop box monitoring, making it seem more like a casual social event than behavior that is motivated by fear of sinister election manipulation.

Timeline and Themes

During Time Period 1, there are two primary spikes of engagement that are centered around @KariLake’s tweet and around @leslibless’s tweet shortly before the primary election in Arizona. The conversation on Twitter consisted almost entirely of support for monitoring drop boxes, with only a small number of users actively posting attempting to counter conspiracy theories that motivated action (green in Figure 1) or framing watching as voter intimidation (purple in Figure 1).

Figure 1: A temporal graph showing the volume of tweets per hour related to drop box monitoring during Time Period 1.

Within discourse supporting drop box monitoring, online audiences participated in several ways that fit loosely into three primary thematic categories: 1) continuing to sow doubt or construct alleged “evidence” of fraud perpetrated by ballot “mules” (yellow in Figure 1), 2) combative rhetoric surrounding monitoring drop boxes, often framing the villains as deviously trying to trick watchers and explicitly connecting drop box watching to 2000 Mules (blue in Figure 1), and 3) drop box watching as a positive social activity (orange in Figure 1).

Although the least prominent in the data we examined, the construction of “evidence” of fraud combined with sowing doubt about the targets of mis/disinformation (in this case ballot drop box security and “ballot mules”) often makes up a large proportion of digital discourse surrounding claims of election fraud. In this case, we scoped our data more narrowly towards actions that may have emerged from conspiracy theories related to false and misleading claims of ballot harvesting and ballot trafficking. Despite this narrowing, a noticeable number of tweets were included in our data that continued to try to build up the evidentiary base in support of the existence of ballot mules and reasons to monitor ballot drop boxes. For example, the tweet below from Michigan Secretary of State candidate Kristina Karamo amplifies a decontextualized video of a person at a drop box, claiming that it is “evidence” of fraud:

2022-07-18 19:49:13 @KristinaKaramo: According to @JocelynBenson we have “no actual legitimate concerns” regarding ballot drop boxes. Her concern are people “radicalized through misinformation”. Here is fraud on camera involving ballot drop boxes she should investigate. Instead, Benson wants to preserve corruption.

In her tweet, Karamo utilizes claims of fraud as a political tool against her opponent in the Michigan election (Jocelyn Benson). Similar to other tweets that amplify “evidence” of alleged fraud, the events in the video are unclear and ambiguous and lack important context (such as where the footage is from, which can impact laws around drop box usage). Despite this ambiguity, this video is taken as clear “evidence” of fraud — even though Karamo says Benson should investigate the events in the video, it is clear that Karamo and many members of her audience interpret the video as evidence of fraud without an investigation being necessary.

The second theme that was prominent in our data related to adversarial framings for why people need to watch drop boxes. This was often accompanied by references to the underlying conspiracy theories surrounding ballot mules. Members of the online audience often supported and/or extended this frame when quote tweeting related tweets, e.g.:

2022-07-18 21:00:00 @[Anonymized]: Good idea. Secret record these because they got away with it for President. You are flat out stupid if you don’t think they will do it for midterms.

<Quote tweet> @KariLake: Ballot Drop Box on the side of some random road in Coconino County.

Potential Mules beware: we are watching drop boxes throughout the state. Smile… 😃 you might be on camera!

In the above tweet, the user supports Lake’s claim that drop boxes are being watched and implies that “they” (Democrats) “got away with” cheating for the Presidential election in 2020 — framing drop box monitoring as necessary to prevent cheating. Additionally, multiple users responded to Lake’s and other tweets using the hashtag “#2000mules,” further cementing the conspiratorial underpinnings of drop box monitoring and making it the most used hashtag in our database during the time period we examined (used 179 times).

The final theme that was prominent during Time Period 1 were tweets related to drop box watching as a casual, social activity. Exemplified most clearly by @leslibless’s tweet (visible in previous section), numerous members of the online audience tweeted supportive, positive commentary about people “tailgating” or having “watch parties.” For example, one member replied to @leslibless’s tweet saying “Outstanding! Love your patriotism!” Tweets that fell into this category often appeared without the combative, often fear-inducing rhetoric common in the tweets that fell into other, more adversarial themes, though the underlying motivations still appeared to be to main drop box security.

Not all of the tweets in the category were wholly positive. There was a range of expression and some accounts leveraged themes of positive community building to motivate further monitoring alongside more adversarial language, e.g.:

2022-08-04 22:00:00 @[Anonymized]: The MAGA movement is taking this Country BACK! 👊 November 8th, you must get out and vote. Sign up to be a poll watcher and throw a tailgate party at every ballot drop box!

<Quote tweet> @bennyjohnson: We are destroying the machine.

Though the sentiment in the above tweet is still positive, it discusses “taking the country back” more adversarially in the same tweet as implicitly referencing underlying conspiracy theories — an interpretation supported by members of this tweet’s audience who replied with hashtags like “#OutvoteTheFraud” or referring to claims that other watchers had already thwarted would-be mules simply by being there.

Time Period 2: Leadup to Midterms, Accusations of Intimidation

In the months since the primary, Arizona has become a talking point in conversations about ballot box surveillance with groups like Lions of Liberty LLC and the Yavapai County Preparedness Team attempting to facilitate organized surveillance campaigns. Concerns that such organization may lead to voter intimidation and voter suppression have driven backlash and legal challenges. This peaked in October with the Arizona chapter of the League of Women Voters filing a lawsuit against the groups, challenging the legality of organized monitoring. Compounding concerns that surveillance may turn into intimidation, on October 21 two armed individuals dressed in tactical gear were present at a Mesa, Arizona ballot drop box. The Maricopa County Elections Department tweeted about the incident, writing that “uniformed vigilantes outside Maricopa County’s drop boxes are not increasing election integrity.”

Prominent accounts and domains

We identified 190,761 tweets related to monitoring drop boxes during Time Period 2, of which 87.3% were retweets and 6.6% were quote tweets, and 27.1% included links to external domains. The table below characterizes the domains that were most frequently linked to from Tweets about the incidents of voter intimidation during this time period. The most shared domain was Democracy Docket, where mostly left-leaning users shared links to articles summarizing updates to an October 24 lawsuit by Arizona Alliance for Retired Americans and Voto Latino. The lawsuit was against Clean Elections USA, Melody Jennings (the founder of Clean Elections USA) and unnamed defendants challenging Clean Elections USA’s alleged voter intimidation practices.

The shares of the Gateway Pundit domain primarily linked to a story about an Arizona voter allegedly covering their license plate when going to a ballot drop box. Other shared links include local (azfamily.com, arizona.votebeat.org) and national (WashingtonPost, Politico, NBC, Vice) news outlets reporting on possible incidents of voter intimidation as well as lawsuits surrounding the events. The Politicus USA domain is a left leaning news site and most of the shares of it in this context are of an article about how those organizing the monitoring of drop boxes did not want to be watched themselves. Finally, tweets using the content.govdelivery domain linked to a joint statement from Maricopa County Board of Supervisors Chairman Bill Gates and Recorder Stephen Richer about drop box watchers in Mesa, Arizona.

Overall, Time Period 2 included much higher levels of engagement as well as more complex conversations than the first time period we examined. In many ways there appear to have been two parallel conversations, one where more liberal leaning audiences, alongside numerous mainstream news outlets, interpreted drop box monitoring as voter intimidation, and another where more conservative leaning audiences continued to amplify many of the same frames discussed earlier. However, in this later time period this conversation adopted a more defensive stance which leaned into descriptions of drop box watchers as “legal” and “peaceful” accompanying rhetoric responding with renewed accusations of fraud and claims of a double standard for voter intimidation.

The most retweeted tweets in our dataset include tweets from left-leaning and/or mainstream media reporters (e.g. Ben Collins at NBC News, 10,306 retweets) and media personalities (e.g., Alex Wagner at MSNBC/Netflix, 9,590 retweets) as well as right-leaning influencers including Dinesh D’Souza (8,699 retweets) and Arizona Secretary of State candidate Mark Finchem (4,150 retweets). Overall, the conversation during the time period we examined was more dominated by reporting and left-leaning interpretations, although right-leaning accounts still received widespread amplification and often responded to tweets from reporters or media outlets by trying to contradict their reporting, often by saying things like drop box monitoring is necessary because “Democrats cheat.”

Timeline and Themes

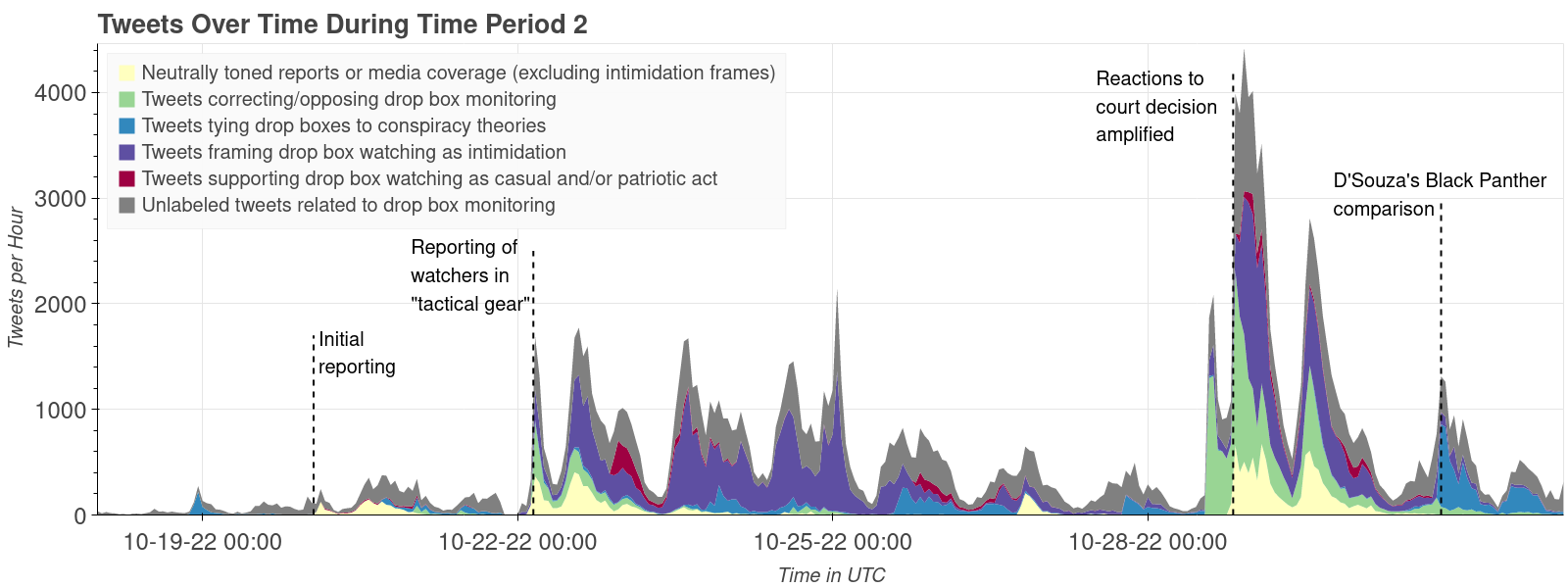

The conversation surrounding drop box monitoring received relatively small amounts of engagement on Twitter between the time periods we examined until closer to the midterm elections when some watchers were accused of voter intimidation. Media coverage of drop box watchers heavily focused on the accusations of voter intimidation as well as the potential for drop box monitoring to have a cooling effect on voters being willing to drop ballots off and/or potential for escalation. In Figure 2, an initial increase of activity is visible shortly after initial reporting on drop box watchers in Arizona, specifically a pair that were described as wearing “tactical gear” and being armed. After initial reports of the pair in tactical gear, online audiences widely interpreted the drop box monitoring as voter intimidation (purple in Figure 2).

Figure 2: A temporal graph showing the volume of tweets per hour related to drop box monitoring during Time Period 2.

Even for audience members who didn’t directly call the monitoring intimidation, many actively criticized either the watching itself or the motivations of watchers (green in Figure 2), e.g.:

2022-10-24 15:04:20 @pbump: Hounding elections officials out of the job. Flooding polling places and drop boxes with "observers" who gin up baseless accusations. Using those accusations as a predicate for blocking an election loss.

The effort to break our elections.

The above tweet exemplifies the general tone of criticisms of drop box monitoring, often interpreting the events in Arizona as part of a larger trend that has the potential to be harmful not just to voters using drop boxes in Arizona, but voters who utilize any method to vote across the country.

The final notable theme within interpretations of voter intimidation was conversation around the race-based history of voter intimidation in the U.S. Audience members compared current drop box monitoring to the racist history of voter intimidation where black and African American voters were often threatened by groups like the Ku Klux Klan to prevent them from voting. The below tweet exemplifies this theme::

2022-10-22 11:00:00 @[Anonymized]: This was a Klan tactic after emancipation until white conservatives found a way to criminalize Black voting again via restrictive state laws.

As coverage and critique spread on Twitter, right-leaning accounts continued to support drop box monitoring, albeit from a more defensive stance that focused on legitimizing drop box monitoring while delegitimizing criticisms. For example, D’Souza posted the following tweet (retweeted 5,987 times) in response to criticisms:

2022-10-30 19:00:46 @DineshDSouza: Remember when the Black Panthers showed up with truncheons to intimidate voters and Obama’s DOJ insisted it was perfectly legal? Keep that in mind when you hear the Left go nuts over patriots peacefully observing dropboxes in case any mules show up

In the tweet above, D’Souza responds to criticisms by reframing the racialized history of voter intimidation as one in which the Black Panthers were the alleged perpetrators of voter intimidation. At the same time, D’Souza also emphasizes that drop box monitors are “peacefully observing” boxes, that they are “patriots,” references conspiracy theories about ballot “mules,” and points to the “Left” as the ones who are going “nuts'' about drop box monitoring. The combined effect of this tweet, and others that reflected similar sentiments, is to legitimize current drop box monitors as patriotic citizens doing their duty to defend elections from the (implicitly delegitimized) left, exemplified by former president Barack Obama and the Black Panthers.

In addition to tweets like D’Souza’s that linked drop box monitoring to conspiracy theories of ballot harvesting/ballot trafficking (blue in Figure 2), other accounts continued to promote the monitoring to in-group members using more positive sentiments, e.g.:

2022-10-22 23:09:30 @leslibless: The Dems are losing their minds over patriots watching ballot boxes everywhere! I call that patriotism. They call it intimidation. 😂😂😂😂😂

In the above tweet @leslibless supports monitoring as a form of “patriotism” and, similar to D’Souza, delegitimizes concerns of voter intimidation by saying “Dems are losing their minds.” Members of the online audience reacted to @leslibless’s tweet by saying things like “Dems are scared,” “we will catch them this time,” and “This coming from the masters of intimidation.” Although the sentiment is still relatively positive, similar to trends visible in Time Period 1, the frame of the positivity was more adversarial in Time Period 2, potentially because of the need to defend drop box monitoring from critiques. Whatever the reason, many tweets with positive sentiments also served to explicitly villainize Democrats, delegitimize concerns of intimidation, and reinforce in-group “patriot” identities.

Due to the gravity of claims of voter intimidation, an ongoing court case determining the legality of drop box monitoring was also discussed in our data. At the time of writing the case is still ongoing, but the largest spike in our data was due to reactions to a decision that it is legal to monitor drop boxes. Reactions from left-leaning accounts questioned the motives of the judge, with some pointing out that he was a Trump appointee and promising an appeal. Right-leaning accounts celebrated the decision as a victory and widely amplified it to their audiences. Although not visible in our data, in a more recent update drop box monitors have been restricted from taking photos or video and are required to stay 75 feet away from boxes, among other limitations.

The Spread on Alt-Tech Platforms

In addition to tracking conversations on Twitter, we analyzed the spread of ballot box intimidation discourse on “alternative” platforms Telegram and Truth Social. We identified four components to conversations as they existed on these platforms:

The publication of 2000 Mules film and the consolidation of the ballot mules narrative.

Calls for action to monitor drop boxes

The posting of “evidence” in the form of photos and videos, purporting to show mules couriering ballots.

The backlash against mainstream reporting of voter intimidation from so-called “ballot watchers,” with claims that mainstream media are manipulating coverage to portray them negatively.

Consolidation of the ‘ballot mules’ narrative on low moderation platforms

In response to the May 20, 2022, public release of 2000 Mules, posts on Telegram lauded the movie as proof that election fraud had occurred, while also discussing where to watch the movie and claiming that “something bigger is coming.” Several posts, shared between a plethora of Telegram channels, called for patriots to take action, such as asking their state officials to investigate the claims from 2000 Mules or researching local voter registration to vet false registrations.

In the lead up to the primary elections, users began to praise candidates such as Kari Lake that echoed fraud claims. Others maintained that steps must be taken so that type of election fraud “must not happen again.” Over the following months, particularly in late July and early August, over a similar time period to Time Period 1 above, some posts called for True the Vote to release all of the data mentioned in 2000 Mules publically before interest faded.

Calls for action to monitor drop boxes

More recently, the false narrative fueled calls for action to protect ballot drop boxes from “mules” for the sake of election integrity. The main protagonist at the heart of these calls for action on Truth Social and Telegram is influencer Melody Jennings, known as “TrumperMel” on Truth Social. Earlier this year, Jennings, inspired by 2000 Mules, founded Clean Elections USA in an effort to prevent ballot stuffing in the 2022 elections.

Clean Elections USA flyer shared by TrumperMel on Truth Social repeatedly.

Originally presented as the “Dropbox Initiative,” Jennings spearheaded the call for action with numerous posts on her Truth Social account, frequently including the above flier. Jennings also promoted Clean Elections USA on podcasts, including Steve Bannon’s War Room.

Screenshot of one of Jennings’ appearances on War Room.

Although Jennings herself does not have a publicly identifiable Telegram account, the narrative has spread on Telegram with users amplifying her calls to action.

Example of Telegram post sharing Jennings’ message on an appearance on War Room. As of November 2, this post was viewed 24.8K times.

Recently, Donald Trump re-truthed TrumperMel’s posts on Truth Social multiple times, including her calls for action to protect ballot drop boxes from the “mules.”

TrumperMel’s post on Truth Social on October 17 was re-truthed by Donald Trump. The post calls “Arizona patriots” to immediate action at ballot drop boxes.

The posting of “evidence” online

As the U.S. midterm elections draw closer and voters begin to cast ballots at drop boxes, activists promoting the “mule” theory are sharing and amplifying images purporting to show the transportation and dropping of fake or fraudulent ballots. On October 16, Jennings posted an image of a man either getting into or out of a car next to a ballot box, asking Truth Social users: “What do you see in the picture?” She claims her team, which was watching the drop box at the time, captured the photo. Jennings implies that because the driver’s license plate is not visible, the individual is trying to hide their identity while engaging in some kind of voter fraud. The post has garnered over 4,000 re-Truths and over 8,000 likes, which is significant engagement for Truth Social.

TrumperMel’s post on Truth Social on October 16. The post amplifies perceived evidence of malfeasance, sowing doubt about a covered license plate.

Telegram channels known for promoting theories around election fraud have shared screenshots of TrumperMel’s Truth Social posts. One Telegram channel with close to 120,000 subscribers re-posted a claim from TrumperMel about ballot stuffing on October 18, 2022 (that had been re-truthed by former President Trump).

Telegram channel promoting “evidence” of election fraud via TruthSocial screenshot.

The tone of these posts varies from explicit descriptions, for example a man pulling “ballots out of his shirt,” to posting images that pose questions which stoke curiosity and calls to action. The pictures shared on TrumperMel’s account are low quality images that fail to substantiate both implicit and explicit claims around election fraud.

Backlash against mainstream coverage of intimidation

On October 20, The Washington Post published an article “Alleged voter intimidation at Arizona drop box puts officials on watch.” The reporting covered allegations of voter intimidation in Arizona from volunteers watching drop boxes and featured a video showing an incident in Mesa, where a man put his ballot in a drop box and was then engaged by nearby individuals (supposedly ballot box watchers.) The article referenced Clean Elections USA, and their efforts in organizing so-called poll watching parties.

A screenshot of TrumperMel’s post responding to The Washington Post article.

The following day, visible in the screenshot above, TrumperMel claimed that the Washington Post’s report distorted the dynamics of the exchange between “lawful” drop box observers and the individual dropping off a ballot. She implies that the video had been strategically edited to give a negative impression of the drop box observer and calls for the full video to be released.

Overall, a few influential right-wing personalities seized on the video provided by The Washington Post as further evidence that 1) mainstream publishers manipulate media to further their agenda, 2) the conduct of drop box observers was lawful, and 3) the conduct of voters at drop boxes is problematic.

Conclusion

It is important to note the contentious nature not just of the activities we describe in this blog post, but of the rhetoric that motivates both calls for monitoring drop boxes and condemnation against those who are watching drop boxes. This is further compounded by the legal gray area surrounding the line between watching ballot drop boxes and perceived and actual voter intimidation. This legal ambiguity combined with the charged history of voter intimidation and highly adversarial nature of conversation resulted in complex interactions that evolved in real time as we conducted our analysis. Below we include three high-level takeaways with regards to the motivations and discourse surrounding ballot drop box watching.

Small number of influential accounts facilitated a participatory process with their audiences to spread false/misleading claims around ballot mules as well as organize and/or support watch parties.

The spread of false and misleading claims surrounding “ballot mules” was heavily participatory in how it was spread and used to mobilize audiences. Although members of the online audience engaged by amplifying claims and alleged “evidence,” the conversations were often driven by a small number of influential accounts. During the time periods we examined, Dinesh D’Souza and Melody Jennings posted the largest number of heavily amplified posts (either on Twitter or other platforms including Truth Social) that either directly spread false or misleading information about ballot drop boxes and “mules'' or, in Jennings’ case, directly helped organize drop box monitoring. Many other prominent accounts participated too, including politicians running for various offices who promoted or alluded to theories surrounding ballot harvesting.

Parallel and adversarial conversations: one where monitoring is primarily framed as hostile intimidation and another where it is framed as a necessary action by patriotic, concerned citizens.

Once reporting on drop box monitoring increased, claims of voter intimidation also increased, resulting in two seemingly parallel conversations discussing the same events from different interpretive frames. Conversations from left-leaning accounts tended to center the activities as voter intimidation while right-leaning accounts tended to ignore the potential for intimidation, framing the monitoring as peaceful citizens performing their patriotic duty. Although within each perspective there was a range of interpretation, more tempered reactions tended to be less amplified and occurred less often, resulting in digital spaces where the primary form of discussion was adversarial.

Within discourse promoting drop box monitoring based on conspiracy theories, the adversarial framing was exhibited through discussion of Democrats as devious enemies who performed actions such as adapting to monitoring by recruiting mobile voting vans — enemies that need to be outsmarted by citizen “patriots.” Within left-leaning discourse, the adversarial framing consisted of discussion where election deniers were trying to undermine democracy based on false and misleading information spread to suppress Democrat votes and/or put their candidates into positions of power.

Mobilizing audiences is an extension of the same processes that spread false/misleading information.

The participatory processes that facilitate the spread of false and misleading information is central to its success at mobilizing supporters towards actions such as drop box monitoring. Visible in our data are audiences that collaborate to produce and amplify “evidence” of alleged fraud, often by reframing events they experienced in their own lives. When influencers and/or political elites such as Melody Jennings, Kari Lake, or Mark Finchem organize actions, or publicly support “grassroots” actions, such as drop box monitoring, the potential for ambiguous or uncertain events to be interpreted as fraud increases, leading to additional “evidence” of fraud being circulated online which in turn motivates further mobilizing. The concern with drop box monitoring is not simply a concern about whether monitoring is legal and conducted in a non-threatening manner — it is a concern about behavior that is motivated not by constructive unease surrounding potential drop box vulnerabilities, but instead motivated by a misinformed, adversarial view of election systems that allows very little room for constructive action by any group other than those considered to be part of the in-group. Instead, the primary outcome of drop box monitoring appears to be more questionable “evidence” of ballot mules to further perpetuate underlying conspiracy theories instead of actually collaborating in maintaining election integrity.