Beyond Twitter: The Election 2022 Social Media Ecosystem

The Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) tracks the activity of “voter fraud influencers” it identified in 2020 across major platforms and several alternatives to Twitter and Facebook.

The game has changed: Since 2020 the social media ecosystem sustaining online electoral misinformation has grown to encompass several platforms, which now host a variety of video, text, and audio content from the identified voter fraud influencers.

New channels of communication: This diversity of content entry points has ensured that screenshots and clips of content are able to circulate — even when the originating account is banned on a specific platform.

More platforms, more problems: This expanded ecosystem poses new challenges for researchers and platforms aiming to minimize the role of misinformation about election fraud.

This Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) analysis was written by researchers at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public.

Introduction

During the 2020 presidential election, the Election Integrity Partnership found that a small number of influential Twitter accounts were highly influential — i.e., creating content that was widely retweeted — in the spread of false, misleading, or unsubstantiated claims that sowed doubt in results of that election, often by alleging or alluding to voter fraud. This original dataset of “voter fraud influencers” was derived solely from data on Twitter, limiting our ability to understand how these popular influencers operated on other platforms. This year, we return to these voter fraud influencers to better understand the full, cross-platform extent of their social media activities, not just on Twitter, but on 10 other platforms (Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, Telegram, Parler, TruthSocial, Rumble, Gettr, Gab), as well as their affiliated podcasts and independent websites.

We find that most of the voter fraud influencers from 2020 are still active on social media today (though not all continue to participate in “voter fraud” discussions), and that their online participation in 2022 spans a wide range of social media platforms. We find that these influencers tailor their media strategies to specific platforms, and most maintain a significant online presence even if they are permanently suspended from Twitter. These preliminary findings show how proactive responses to election misinformation in 2022 and beyond will need to address this reality of multi-platform influencers.

Background: The Changing Ecosystem

Prior research and reporting has identified two primary factors that affect the social media ecosystem for election misinformation in 2022: 1) changes in the popularity of individual platforms, and 2) responses to policy enforcement on mainstream platforms.

The first factor is that some platforms are growing more rapidly than others. TikTok, for example, was an emerging presence in 2020, but has since seen enormous growth in its user base, and, according to research by Pew, is increasingly used as a source of news. Video-sharing platform Rumble has also seen significant growth, as has the message-sharing platform Telegram. Meanwhile, user growth has, by comparison, stagnated at some of the largest platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, although they remain popular in the United States.

The second factor is the actual and perceived increase of platform moderation — i.e., policy enforcement — of misinformation and threats of violence related to misinformation since the 2020 election. In response to the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, some platforms, like Parler, were severely sanctioned by internet service providers. As a result, they seemingly lost much of their active user base. In some cases entire communities were targeted to be banned from mainstream platforms, such as the QAnon conspiracy community, which experienced moderation — and widespread suspensions — from almost every mainstream platform. The perception of increased moderation of far-right views created opportunities for what the Pew Research Center has called alternative social media platforms to attract these fringe audiences. The owners of emerging alternative social media platforms like Telegram, Gettr, Rumble, and Truth Social claim to moderate content much less often than mainstream platforms, especially for moderation of far-right content. This has likely helped fuel participation and growth from disaffected far-right users of other platforms.

Data & Methods

To understand the cross-platform presence of Twitter-based voter fraud influencers in 2022, we analyzed the cross-platform presence of 34 Twitter accounts we previously identified in published research as repeatedly influential in the spread of misleading claims about the 2020 election. In that research, through a real-time curation process, we identified a hundreds of false, misleading, or unsubstantiated stories that sowed doubt in election procedures or results, and then identified Twitter users who had repeatedly participated in the spread of these stories and been retweeted over 1,000 times each time they did. Here, we refer to the accounts that were repeatedly influential in the spread of these stories as “voter fraud influencers” — because the vast majority of these stories either alluded to or explicitly alleged voter fraud.

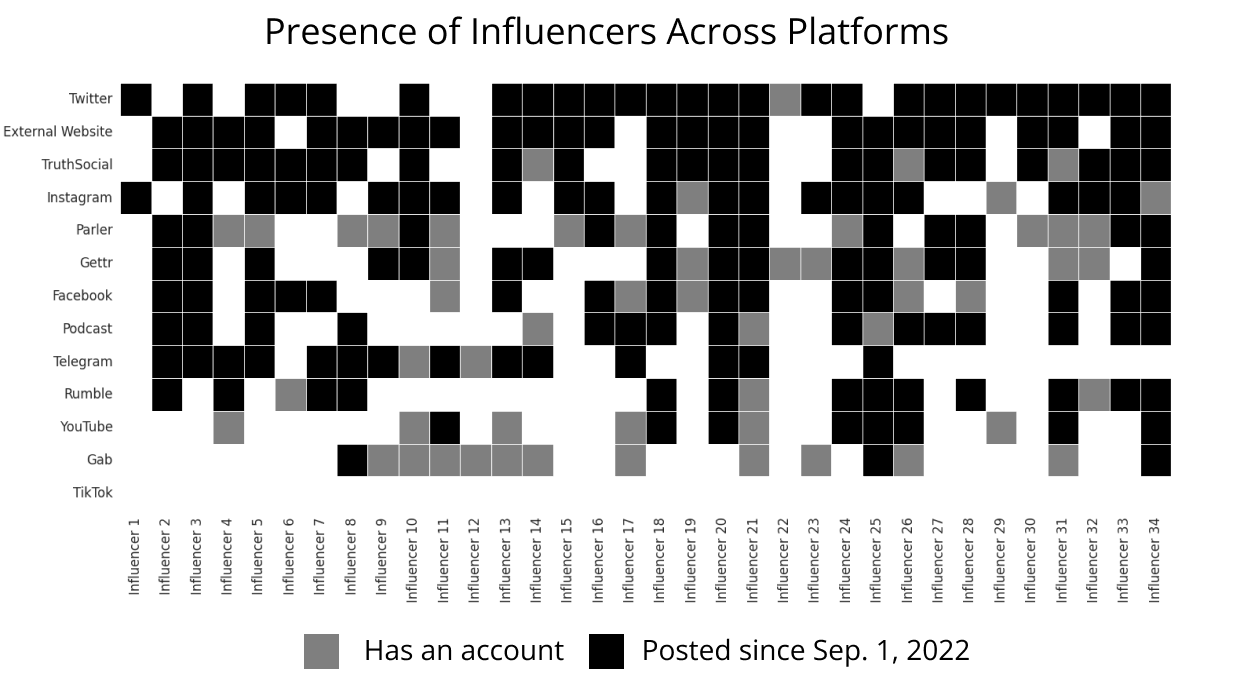

In this post, we assess whether each of these accounts had either a verified account on one of 11 different social media platforms as of November 3, 2022, or an account that was referenced or hyperlinked from one of their verified accounts. We also assessed whether they maintained independent websites where they published content, such as the hyperpartisan news website, The Gateway Pundit, and podcasts that they host independently or on podcast platforms (e.g., Apple Podcasts, Spotify, etc.). On each of these platforms, we noted whether the accounts had created any posts after September 1, 2022, as a measure of whether they were recently active on that platform or not.

Tailoring Their Content: Influencers Specialize Across Platforms

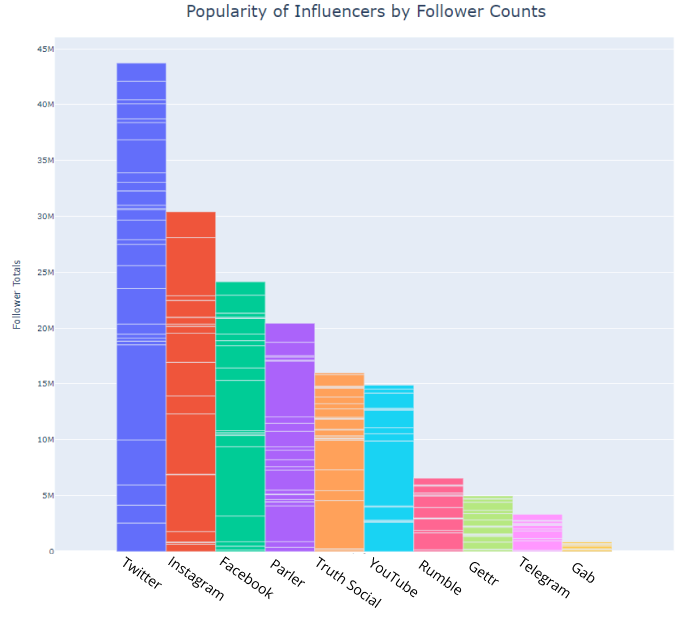

The follower counts of different influencers by platform in our dataset. Lines in the bar plots separate the follower counts of different voter fraud influencers. TikTok is left out due to lack of data. Note that some followers may not be active, or may not be authentic users. Specifically, Parler is said to have far fewer active users than other alternative social media platforms, despite the follower totals shown on this graph. Note also that this data describes influencers we identified via Twitter, who naturally may have bigger platforms on Twitter than other platforms.

After the 2020 election, former President Donald Trump was the most followed voter fraud influencer on Twitter based on our research. Since his account was banned, that mantle has been taken up by his son, Donald Trump Jr. However, this is only on Twitter, and the relative popularity of these influencers vary elsewhere. All 34 of the influencers that we analyzed had at least one account on a platform besides Twitter, and 33/34 were actively posting on these accounts as of September 2022. However, most influencers selected a subset of platforms to primarily post to, and the amount and type of content that they posted between platforms varied.

A visualization of how many voter fraud influencers are active on each platform. Black squares represent users who are currently posting on this platform. Gray squares represent users who have an account, but have not posted since September 1, 2022. Empty squares represent users with no account we were able to verify on this platform. We could not verify the last post date for many websites, and have marked them all as black squares in this visualization.

Variances in platforms’ affordances and cultures can encourage influencers to tailor how they produce content and engage with their audiences. Just as sites like Rumble and YouTube primarily encourage video content, Instagram forefronts multimedia content and non-political “lifestyle” content. We see influencers share more multimedia meme content on Instagram, in addition to a greater share of pictures of themselves with family members or enjoying hobbies. These posts are then mixed with politically-oriented posts about elections. On Instagram, several influencers make use of the “Stories” feature, allowing them to post daily images and videos which disappear after 24 hours.

The Lasting Presence of Voter Fraud Influencers Suspended from Twitter

After the January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, seven of the voter fraud influencers identified in 2020 were permanently suspended from Twitter based on their independent policy enforcement mechanisms. They were suspended for violating several of Twitter’s policies, including those on election misinformation, incitement to violence, and fraudulently operating multiple accounts. Despite these bans, the expansion of other platforms allowed some of these users to find homes on platforms with more permissive moderation policies.

Three of the voter fraud influencers suspended from Twitter have continued to be active across many other platforms. Accounts for media website The Gateway Pundit, James O’Keefe, and O’Keefe’s media organization, Project Veritas, have continued to post on almost every platform we surveyed. Project Veritas in particular has a relatively high follower account among the voter fraud influencers on Telegram and YouTube, though they also post content on Facebook, Instagram, Parler, Truth Social, Rumble, Gettr, and Gab.

The Gateway Pundit also posted noticeably different content depending on the platforms. For example, on October 31, 2022, the Gateway Pundit published a story to their website suggesting that “Democrats'' had organized “cheating” in several states ahead of the 2022 midterms. They shared their story on their official account on Telegram, Parler, Gettr, and Truth Social, but not on Facebook, where they posted other stories. Operating on different platforms with different moderation preferences may allow popular accounts to tailor more extreme content for alternative social media platforms, while publishing safer content on the mainstream platforms.

Two other influencers, both prominent in the QAnon conspiracy movement, have been restricted to only alternative social media platforms since their suspension from Twitter and many other mainstream platforms. One of these accounts, which once had more than 400,000 followers on Twitter, now maintains an active presence on Gab, Telegram, Truth Social, and Rumble, continues to promote the QAnon conspiracy theory on these platforms, and speculates about the “election theft machine” in one of their recent posts on Truth Social. The other account had initially joined many other alternative social media platforms in the wake of their suspension, but has since stopped posting under this name on any platform as of September 2022.

At least one influencer maintains a presence on several mainstream and alternative social media platforms, but has largely stopped engaging with political content and instead focuses on their entrepreneurial ventures. This leaves the final banned voter fraud influencer: former President Donald Trump. Trump responded to his being banned from mainstream platforms first by releasing personal written statements to the press, and then by founding his own alternative social media platform, Truth Social. As we document in the following section, while Truth Social has a smaller audience than mainstream platforms, the content he posts there travels far and wide across many other platforms via screenshots.

Unconstrained Content: Personal Websites, Podcasts, and Screenshots

As of November 3, 2022, six Twitter-based voter fraud influencers from 2020 have podcasts that appear in Apple Podcasts “Top 100 Podcasts in Politics.” Three are highlighted in yellow in this screenshot.

While the voter fraud influencers still use social media posts to communicate, expansion beyond social media platforms has allowed them to diversify their channels of communication through use of independent media ventures, such as news websites, podcasts, and radio shows. All of which can be shared or spliced across any social media platform.

Project Veritas and the Gateway Pundit, two accounts suspended on Twitter, have their video content and news content shared by other Twitter users. We have obscured the screenshots as we have not verified the claims made in these posts.

For example, of the 34 voter fraud influencers we identified in 2020, 18 currently host podcasts, and at least 10 of those who do not host podcasts have done guest appearances on the others’ podcasts. Many of these podcasts are hosted on podcast distribution services, and then later clipped and posted across a variety of media platforms. Some influencers’ social media accounts predominantly post clips from their podcasts and radio shows, which are then shared by other users on every other platform. In addition to podcasting services, many voter fraud influencers from 2020 either directly represent, own, or work for media enterprises. These include The Gateway Pundit, Judicial Watch, Human Events, Breitbart News, Project Veritas, Just the News, and The Federalist. Links to these websites are often posted by other users across social media platforms, without the original accounts of any voter fraud influencers involved.

Examples of content screenshotting from one platform to another.

Finally, the popularity of posting screenshots on social media means that influencers do not need an account on a given platform for their content to reach users. Some voter fraud influencers, for example, use Instagram simply to post screenshots of their and others’ posts from Twitter. Other accounts, either run by fan accounts or by unverified authors, exist to amplify voter fraud influencers’ current or “greatest hits” content from other platforms. Posts from former president Donald Trump on his platform frequently find their way to Twitter and other social media platforms despite his active ban. While their reach is almost certainly not as far as if Trump had been posting natively to Twitter, it remains a way in which influencers can transmit information from the alternative media ecosystem to the mainstream.

Takeaways: It’s More Than Just Twitter and Facebook

Leading up to the 2022 U.S. midterm elections, election-related content from 2020 “voter fraud influencers” is increasingly distributed across many platforms. This may point to the partial success on the part of mainstream platforms that have adopted stronger moderation responses to influencers who repeatedly post content sowing doubt in electoral processes. Twitter independently banned seven users that we had originally labeled as “repeat spreaders” of election misinformation in 2020. Others, now faced with the prospect of increasing moderation by mainstream platforms on which they have the largest potential — and often actual — audiences, have had to adapt and tailor their content for different platforms, potentially withholding content most likely to violate policies on “big tech” platforms. Instead, they post this content on alternative social media platforms.

There is significant peer-reviewed, scientific research to suggest that “deplatforming” — the act of permanently banning an influential user or groups of users from a platform, often for repeated or especially egregious violations of platform policies — works to reduce the reach of harmful content on the platform in question (Chandrasekharan et al., 2017; Jhaver et al., 2021). There is also emerging empirical evidence which suggests that being confined to alternative, low moderation platforms decreases the overall reach and engagement of content produced by the influencers in question (Rauchfleisch and Kaiser, 2021).

Despite their removal from mainstream platforms, we found that many influencers we had marked as voter fraud influencers on Twitter now have sizable audiences on alternative platforms, the most popular of which appear to be Telegram and Rumble. Content on these platforms may have less potential to “go viral” given the smaller audience size and, in the case of Telegram, lack of algorithmic amplification. However, these platforms do not exist in isolation from the rest of the information ecosystem, as evidenced by several influencers’ presence across both mainstream and alternative platforms, as well as the sharing of screenshots, audio snippets, and video clips across platforms. An October 2022 Pew Research poll found that only six percent of Americans regularly obtain news from at least one of seven alternative social media platforms. Nearly two-thirds of those that regularly frequent these platforms, however, say that they “have found a community of like-minded people” there, suggesting that they provide loyal user bases for influencers to tap into.

The ability of these influencers to build up large followings across different alternative platforms challenges some intervention strategies for curtailing the spread of misinformation, such as prebunking, fact-checking, and context flagging. These interventions are unlikely to be implemented in alternative, low-moderation environments. Furthermore, we note the growing importance of new media platforms – namely podcasting and video streaming services – in the election misinformation landscape. Compared to text, audio and video are time-consuming mediums to both moderate and research, but they appear to be a key way that influencers promote their brands, produce, splice, and remix content to share widely on other platforms. Furthermore, few if any of these platforms offer the level of transparency to researchers that Twitter historically has, limiting external parties from being able to understand their moderation practices.

The last challenge we will note is the time-consuming and difficult-to-automate work of linking influencer profiles across platforms. Platform verification methods vary widely, and many influencers may hold accounts on platforms where they are unable to be verified. Platforms may even verify and create accounts for users who have never been active there, such as Gab did with Donald Trump. We adopted a strict standard that required us to confirm that an account on another platform was indeed the same user, either by having a verified profile on the platform or having a direct chain of links to that account from verified sources. One drawback of this method, for example, is that no account on TikTok meets that criteria, despite some of these influencers likely running non-verified accounts that we identified. This is especially true when we consider the presence of fan accounts, which post content from a different influencer for monetary or social gain, and only sometimes identify themselves as such. Future research and reporting must be wary of these pitfalls in cross-platform identification.

Summary Points

Election fraud influencers continue to thrive on mainstream and alternative platforms, building up sizable audiences. Many use a combination of platforms, often in complementary ways. Even when a specific account is not present on a particular platform, its audiences may cross-post content there from other platforms.

Given the growing influence of new alternative platforms, where policies guiding moderation are often less restrictive, to understand online discourse around events like elections, researchers need to take a cross-platform approach.

Policymakers should consider instituting platform transparency legislation where platforms are required to make available — at minimum — aggregated data on follower/following statistics, post frequency, and engagement metrics available to researchers via application programming interfaces (APIs).