Platforms of Babel: Inconsistent misinformation support in non-English languages

Author: Vanessa Molter, Graphika

Contributors: Carly Miller, Elena Cryst and Matt DeButts, Stanford Internet Observatory; DFRLab

Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok have developed and are enforcing policies aimed at countering misinformation around the US elections, including labeling misleading or false content, providing additional information, or removing content. However, for non-English-language content, there are two distinct issues with platform enforcement: 1) lacking capacity to review and take action on problematic content in these languages, 2) the absence of additional context labels and information in these languages, particularly on YouTube and Twitter.

This means Americans speaking languages other than English are disproportionately vulnerable to seeing election-related misinformation. Given that there are an estimated 10 million American voters who do not speak English, we assessed a range of platforms on their implementation of election-related misinformation in other languages. We focus our assessment on Spanish and Chinese, as these are the second (41.5 million speakers) and third (3.5 million) most common languages in the United States after English. Snapchat, Nextdoor and Pinterest have policies in place against election-related misinformation, but as their enforcement is limited to removal of misleading content our analysis here focuses on those mentioned: Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and TikTok.

Key Takeaways:

Although various social media platforms have developed and are implementing policies aimed at countering election-related misinformation, efforts show significant gaps in languages other than English.

There are two distinct issues with enforcement of existing platform policies on non-English content:

1) lacking capacity to review and take action on problematic content

2) the absence of additional context labels and information in non-English languages, particularly on YouTube and Twitter

Facebook and TikTok offer labels and voter information pages in multiple languages.

We recommend that platforms emulate Facebook and TikTok’s measures and urgently translate existing labels and added context. This will help inform the over 10 million eligible American voters who do not speak English and can be implemented with automated translation tools, which allows platforms to act quickly.

We also recommend that platforms expand their attention to non-English languages and enforce misinformation policies in other languages widely spoken in the United States, such as Spanish and Chinese.

Background

According to the Census Bureau, there are at least 350 languages spoken in U.S. homes. Many Americans rely heavily on languages other than English, which is why federal law requires some localities to offer ballots and other election-related material in non-English languages. In some states such as California, state law also requires additional languages to be offered. As a result, California ballots are offered in 14 languages; in Cook County, Illinois, which includes Chicago, voters can request ballots in 12 languages. New York City recently expanded voter registration to 16 languages.

Of the 35 million adult U.S. citizens who speak a language other than English at home, 31 percent are not proficient in English, indicating that over 10 million eligible voters are not proficient in English. Non-English speaking citizens are therefore uniquely vulnerable to being targeted and leveraged by various actors seeking to seed election-related misinformation.

Problem 1: Platform enforcement on non-English language content is lacking, particularly on Twitter and YouTube

Non-English election-related misinformation on Twitter and YouTube lack labels or other enforcement action. We found several examples of misleading or false election-related content that has gained some traction on Twitter in both Spanish and Chinese and on YouTube in Chinese - this content has not been removed or labeled by the platforms.

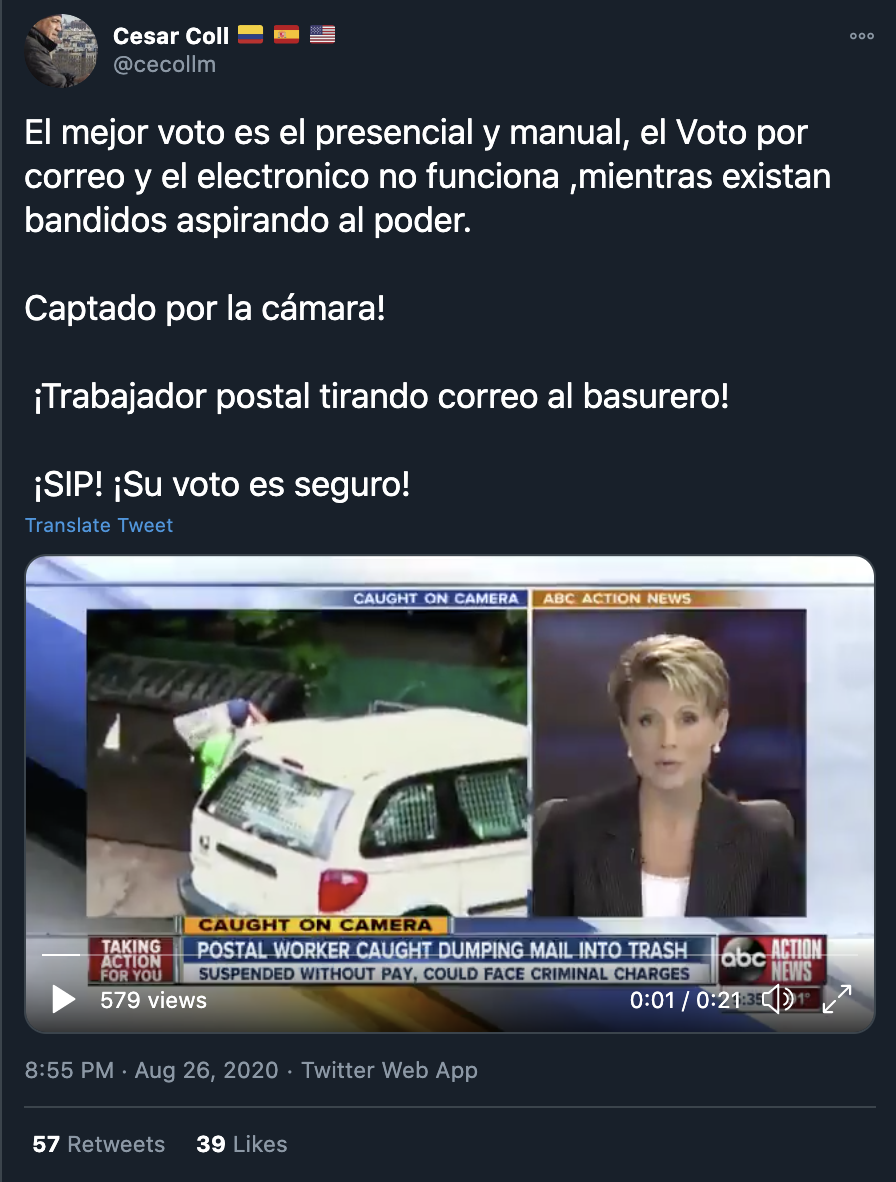

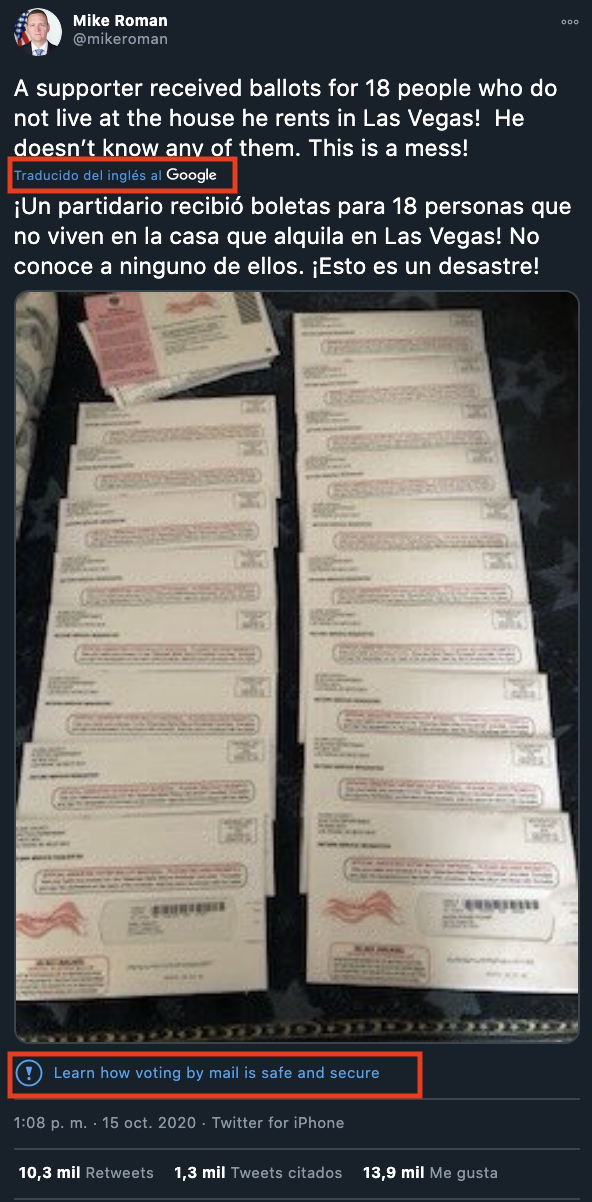

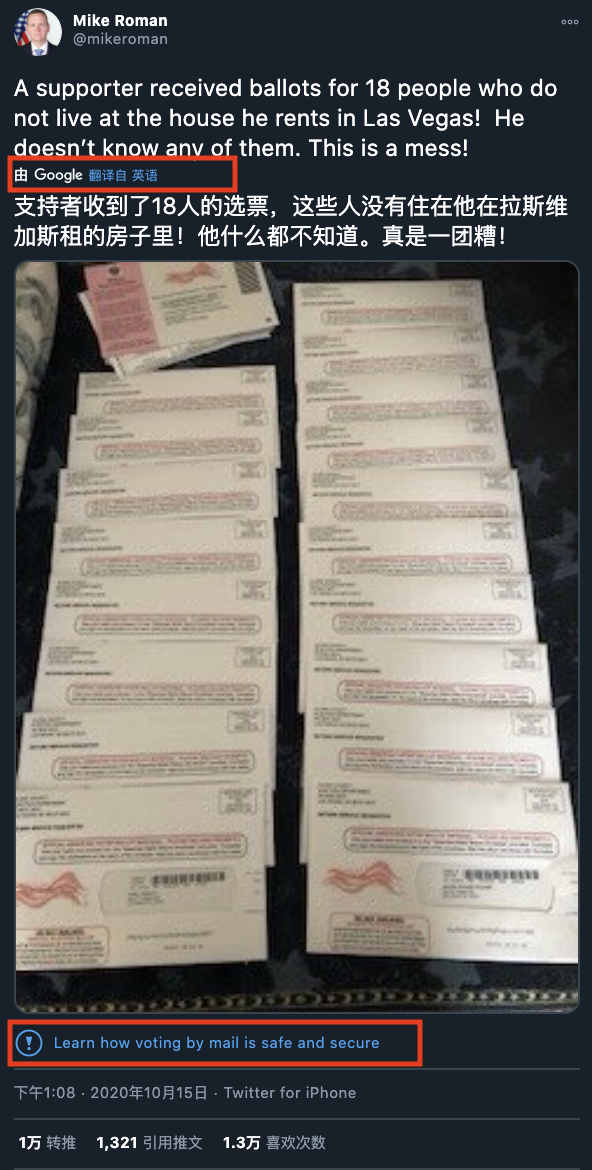

For example, multiple Spanish-language Tweets cast doubt on the safety of voting by mail, such as one Tweet from September 28 claiming to show “proof of how votes are bought for the Democrats” or another from August 26 saying voting by mail does not work. Similar content can be found in Chinese, with one Tweet repeating claims previously made in a labeled English-language Tweet. None of these Tweets have been labeled.

Figure 1: Left: Spanish-language Tweet claiming voting by mail does not work. Right: Retweet in Chinese repeating false claims made in a labeled English-language tweet. Neither of the pictured Tweets has been labeled.

According to YouTube’s policy, the platform curates information about political news and events by “raising up authoritative voices” such as news sources for specific search terms, although YouTube does not specify which languages this is implemented in. In Spanish, multiple search terms that may cast doubt on the safety of mail-in ballots (e.g. “voto por correo no es seguro” [voting by mail is not safe]) show exclusively results from verified accounts such as CNN en Español or Voz de America explaining the safety of voting by mail. In Chinese, however, similar search terms (e.g. 邮寄投票不安) surface videos on the first results page repeating false allegations about election fraud related to mail-in ballots, arguing that Nancy Pelosi would get the chance to be president if there was a delay in getting mail-in results. For Chinese-language users, the video is not labeled (see below on discussion of Problem 2).

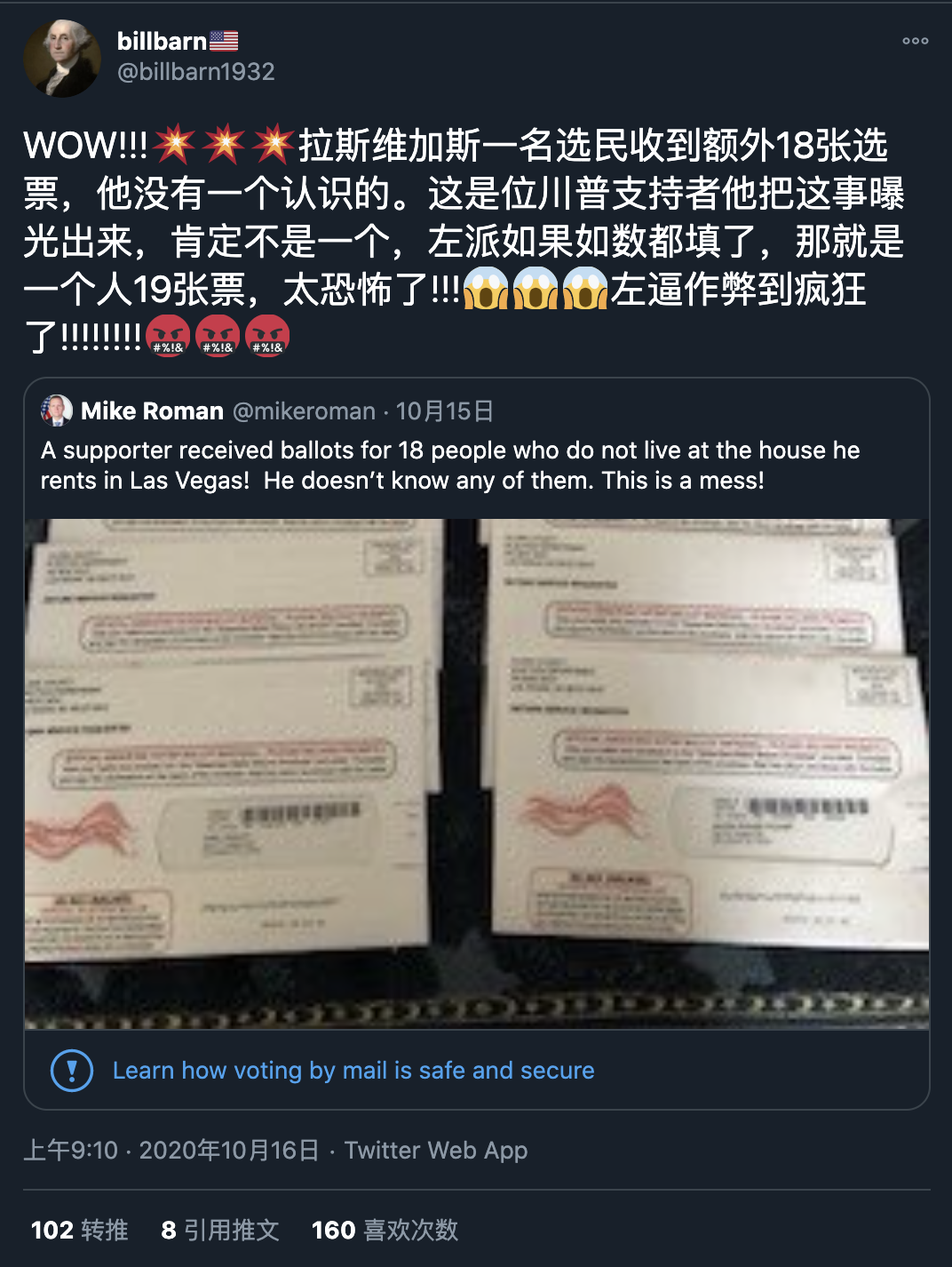

Additional searches surface further misleading content, such as a Chinese-language video with over 4k views claiming that people can vote twice if they use mail-in ballots, or another video with over 11.5k views claiming fake IDs may be used by ineligible voters to vote fraudulently. Neither video is labeled.

Figure 2: Top: YouTube video claiming people can vote twice in the mail-in ballot system with over 4k views. Its title includes “U.S. election fraud method“ (美国大选选票造假手法). Bottom: YouTube video on mail-in vote fraud allegations with over 11.5k views. Its title includes the claim that “mail-in vote might be fraudulent” (邮寄选票可能舞弊). Neither video is labeled.

Problem 2: When election-related misinformation is labeled or given additional context, this information is provided only in English

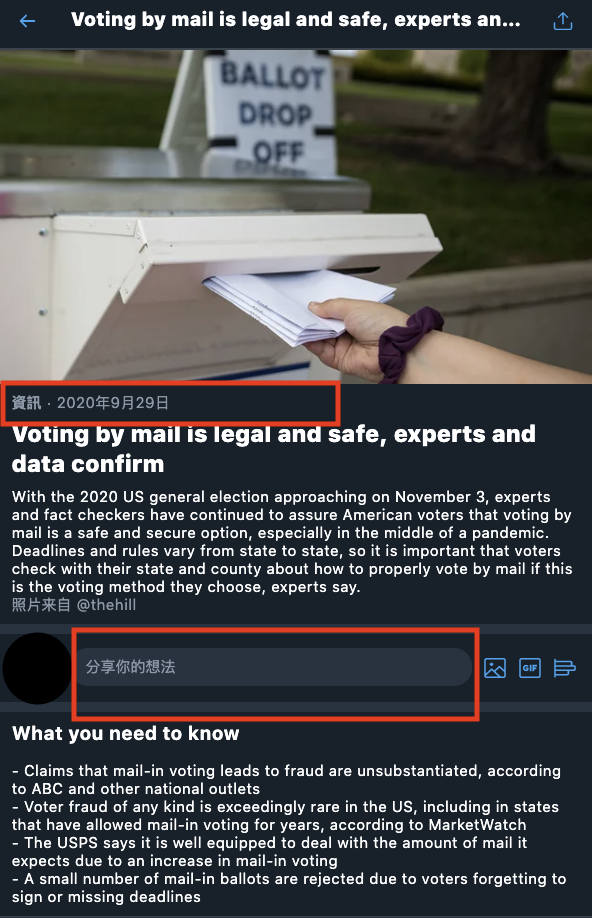

On Twitter and YouTube, we find that both labels on English-language content identified as false or misleading, as well as linked pages providing additional information as context for the misleading post or video are only provided in English.

Although Twitter offers a Google Translate button for Tweets, these translations are not offered for labels or linked information provided by the platform itself. For example, a Twitter user browsing in Chinese (simplified) or Spanish can easily translate Tweets from English even if they are sharing false or misleading information. The label identifying the Tweet as misleading, on the other hand, cannot be translated and is easily ignored if the user does not read English. In another case, a Chinese-language Tweet identified as misleading and labeled by Twitter is labeled in English, thus adding no context for non-English language users despite being the Tweet’s target audience.

Figure 3: Non-English language Twitter users can translate Tweets that are labeled by clicking the “translate” button (see upper red box), whereas the label adding context to potentially false claims in the Tweet does not get translated.

Figure 4: Misleading or false Chinese-language Tweet with English-language label

Even if the user clicks on the label to see further information, the resulting page is only available in English. As on the label, there is also no Google Translate button for this context.

Figure 5: Example of where Spanish-language (left) and Chinese-language (right) users on Twitter are redirected when clicking an information label. Information is provided in English, there is no translation button.

YouTube's policy is to add context for U.S.-based voters searching for election-related terms in English or Spanish, adding a label to YouTube search results that links to Google search results on for example how to register to vote. However, non-English speakers are similarly ignored when it comes to labeling election misinformation: While English-language users on a YouTube video containing misleading or false information are shown a label which redirects users to the Bipartisan Policy Center, users with their language set to Spanish (United States) and location to United States are not even shown a label on the same video. On a separate video making false claims in Chinese, English-language users are shown the same label, yet the label is not shown to users with their language set to Chinese.

Figure 6: Top: A labeled YouTube video redirecting users to the Bipartisan Policy Center offering information on voting by mail. Bottom: For Spanish-language YouTube users, the label disappears.

Figure 7: Top: English-language users are shown a label on a Chinese-language video containing election misinformation. Bottom: Chinese-language users are not shown any label.

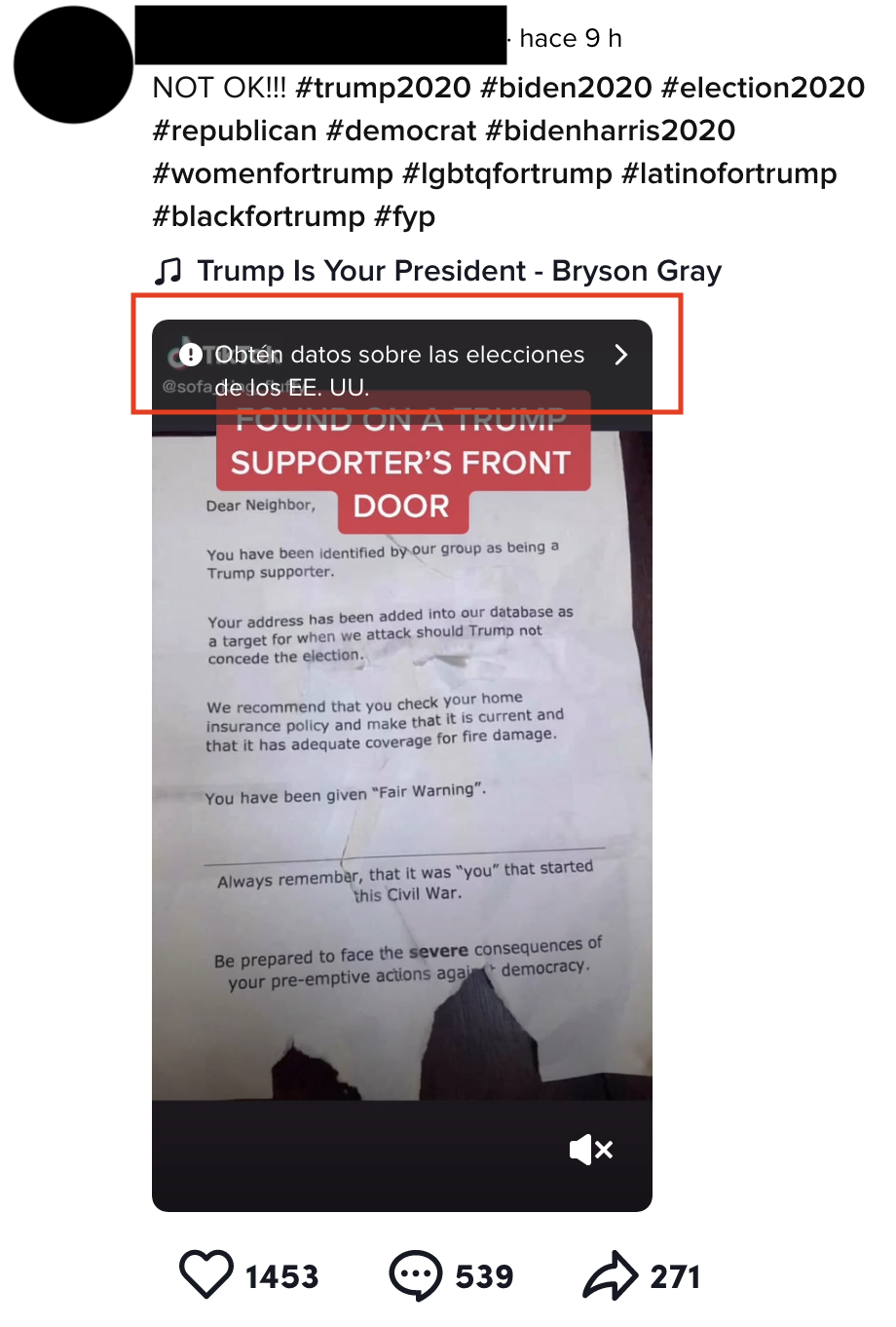

It is possible: Facebook and TikTok have translated labels and provide voting information centers in multiple languages

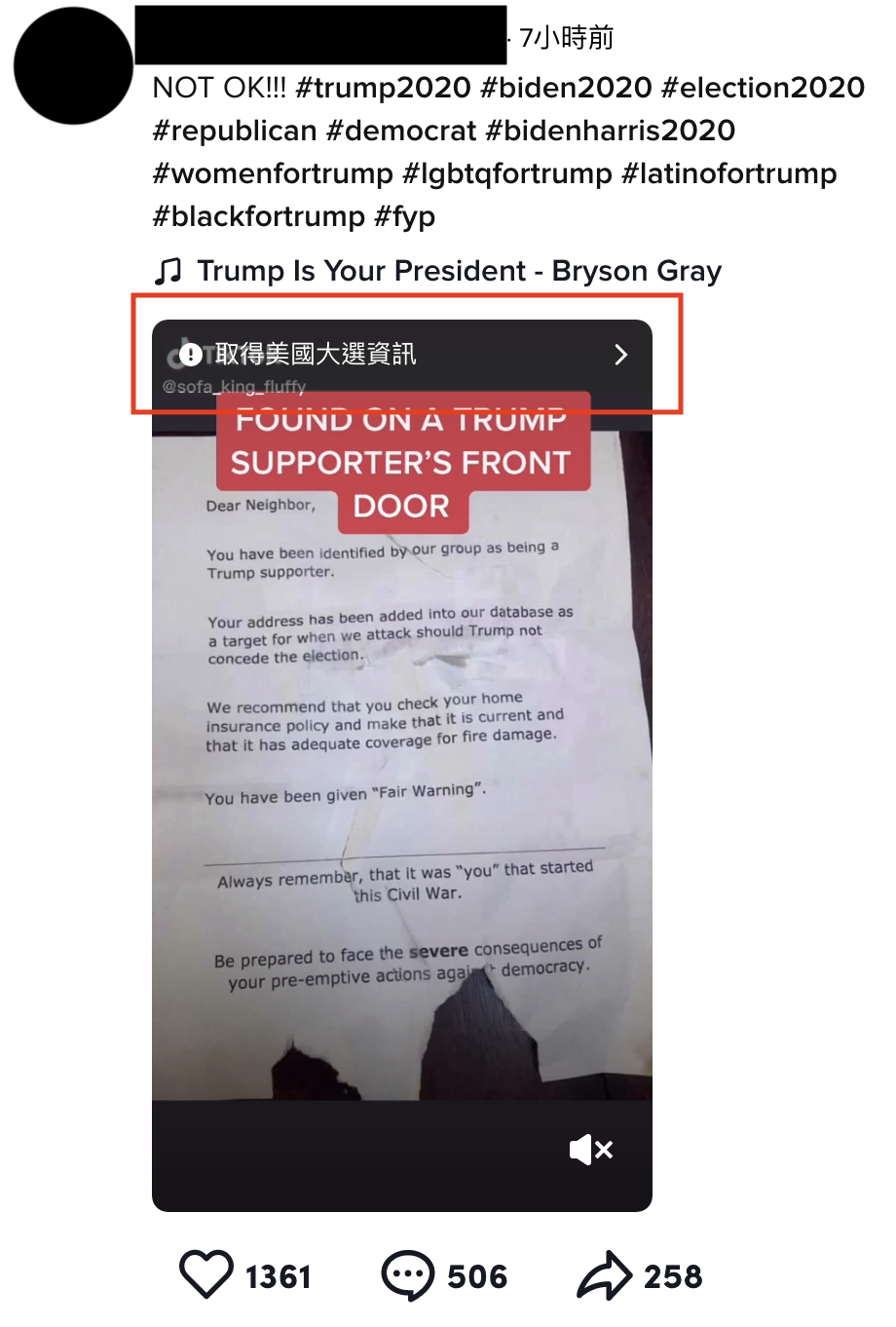

Conversely, Facebook and TikTok are more conscientious of non-English language users in their efforts at countering election-related misinformation. TikTok offers translated labels on its short-videos depending on which language a user has selected. If an app user clicks on the label offering “information on the U.S. elections,” TikTok redirects the user to the platform’s new elections guide, available in 47 languages. For web users, the multilingual labels redirect to a page offered only in English with no option to specify or change language preferences.

Figure 8: TikTok translates labels into the language of the user on both web and in the app, including Spanish (left) and Chinese (traditional, right).

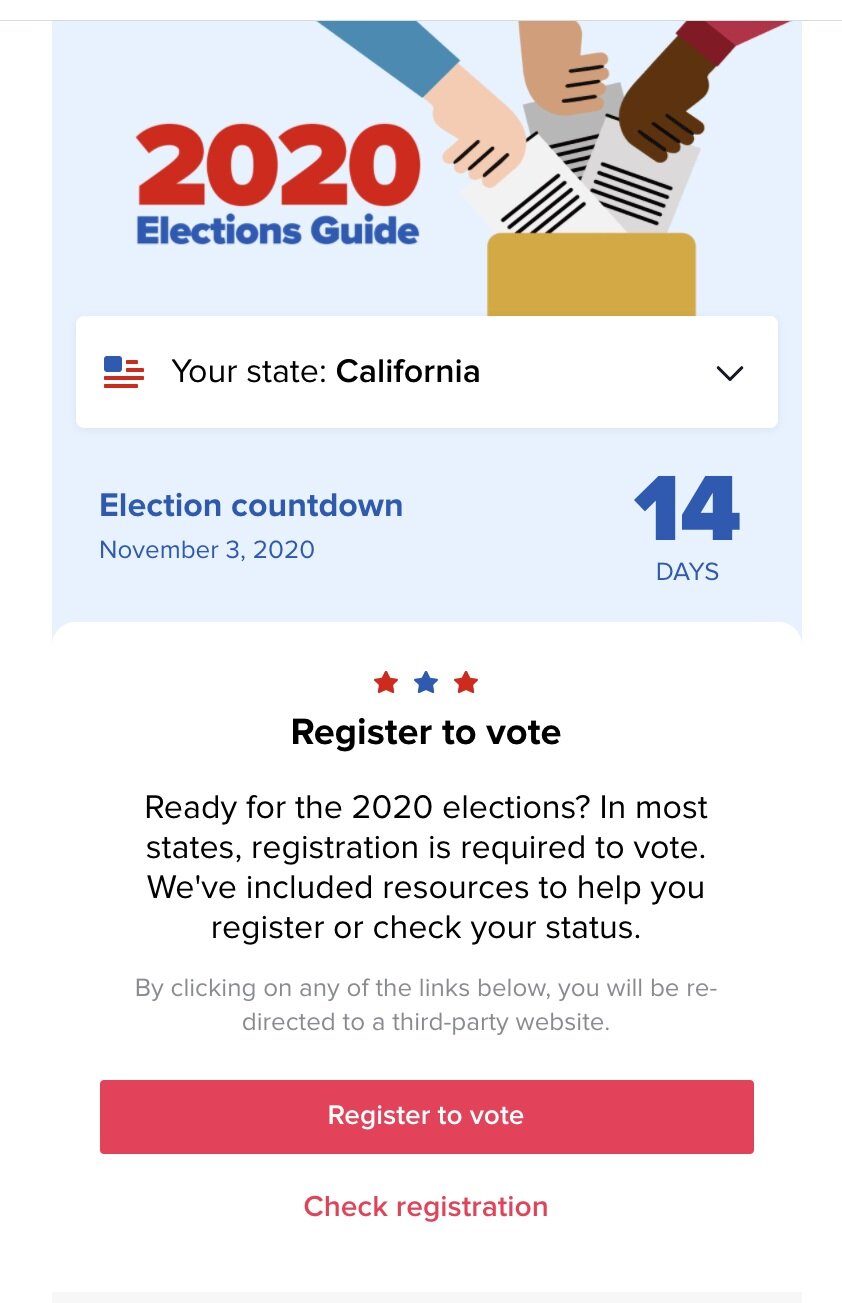

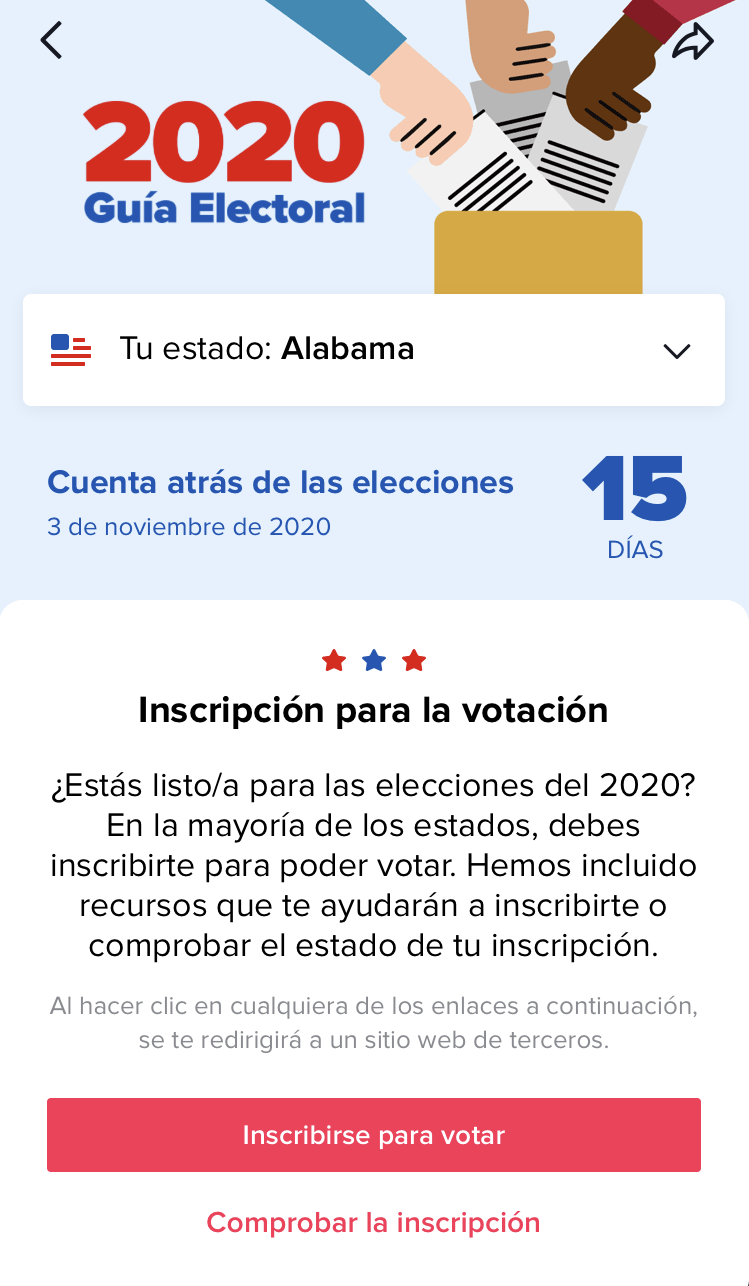

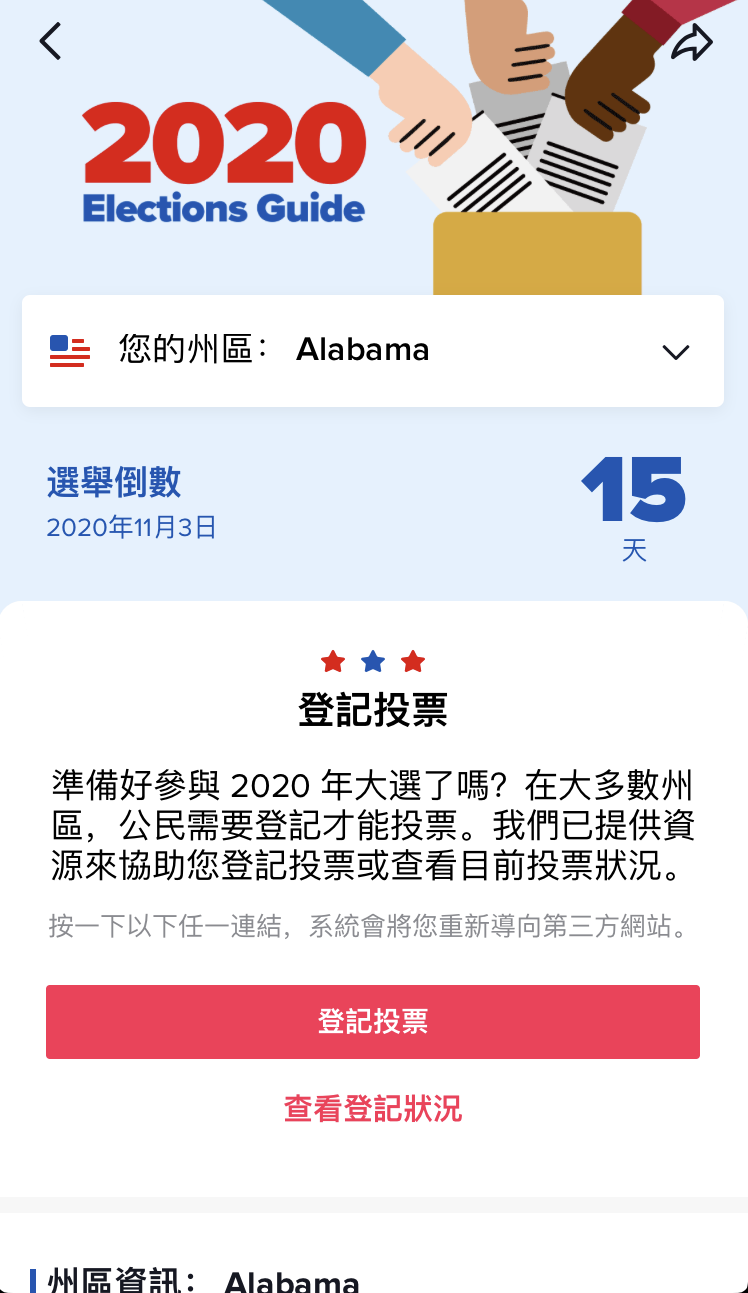

Figure 9: Left: Both labels redirect web users to an English-language information page, the page does not offer a “translate” button. Right: App users are redirected to a voting information center matching their language settings.

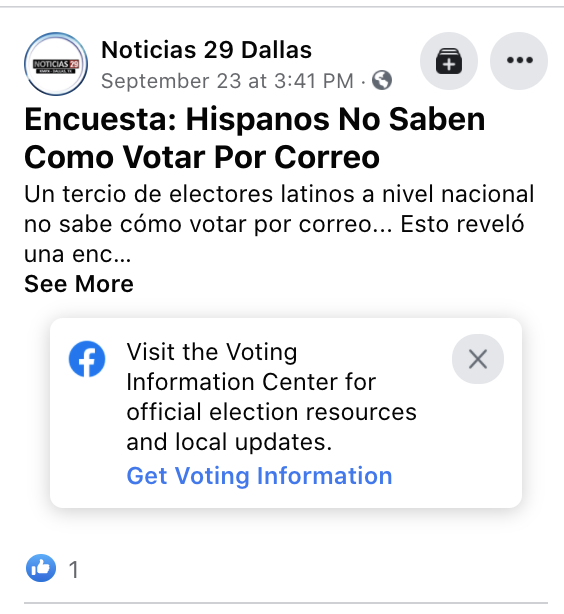

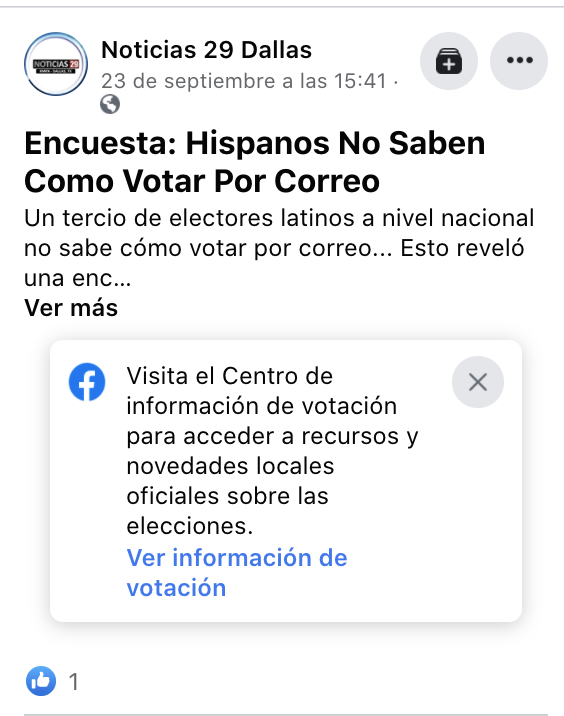

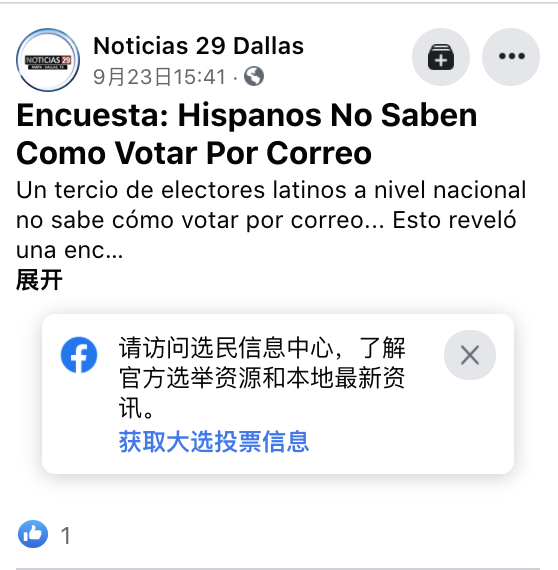

Similarly, on Facebook, all problematic content we could identify had been labeled, with labels automatically translated into a variety of languages depending on which language a user has selected in their account preferences. These links direct users to Facebook’s voting Information center which is automatically displayed in the language a user has set their account to on both the web and in the Facebook app.

Figure 10: Facebook labels are automatically set to the language which a user has set their profile to, here from left to right: English, Spanish, and Chinese label on Spanish-language content

Figure 11: Facebook’s voting information center is displayed in Spanish (left) and Chinese (right)

We could not find unlabeled misleading content in Chinese or Spanish on TikTok or Facebook. This does not mean there is no such unlabeled content but could indicate more platform attention on this issue.

Both TikTok and Facebook could further improve the quality of their voting information by linking to off-platform websites with voter information depending on users’ language preferences. For example, a user in California with their language set to Spanish would ideally be directed to the Spanish-language version of the California’s voter registration page (rather than the English-language version). Currently, all users appear to be redirected to the English-language website of their state even when other language versions are available. This is a minor point of criticism as, for example, California users can click their language preference on the state’s website, but redirecting to a page with the user’s preferred language would allow for a smoother experience for the user. In addition, TikTok should offer translation buttons or automatically implemented translations of the elections guide as well as its safety center for web users.

Recommendations

First, given there are only a few remaining days before the election we recommend platforms emulate efforts from Facebook and TikTok and translate their existing labels into the most-commonly spoken languages in the United States, including Spanish and Chinese. These crucial translations will add context for non-English speakers when they read a translated or watch a subtitled misleading piece of content. Translating labels also adds context to foreign-language re-shares of content such as retweets in Chinese as in the example above, without any additional effort for detecting and labeling new content. Given the relatively straightforward task of translating existing labels, we think platforms like YouTube and Twitter should implement this change quickly and as soon as possible.

Second, platforms should offer translated versions of their information pages, like TikTok and Facebook are already offering. Similar to translated labels, these translated information pages would add context for non-English speakers. This translated content could rely on imperfect but easily implementable optional machine translations such as offering a Google Translate button by default, helping to inform non-English speakers in the remaining lead-up to November 3.

Last, platforms should increase their efforts at finding and countering election-related misinformation in non-English languages. As mentioned above, over 10 million U.S. citizen adults (4.7 percent of potential voters) do not speak English. Like others, these voters should not be subject to an information environment that lacks checks and context and where misinformation runs rampant, which could otherwise undermine their trust in electoral processes and possibly suppress voter turnout.