Analysis of Wednesday’s foreign election interference announcement

Authors: Jack Cable and David Thiel, Stanford Internet Observatory

Contributors: Carly Miller, Renee Diresta, Alex Stamos, Stanford Internet Observatory

This week has seen a flurry of activity related to potential voter suppression, starting with the sending of threatening emails, purportedly from the Proud Boys, to voters in several states; the release of a video purporting to show the hacking of voter registration databases; and finally the attribution of this activity to the Islamic Republic of Iran by the United States Government.

In addition to their announcement of Iranian involvement, the FBI also announced that both Russian and Iranian actors had separately obtained US voter information. The reporting of this activity has raised many questions, and we will use this post to outline what we know and what we suspect about these incidents.

The key takeaways:

The technical evidence supports the assertion that the “Proud Boys” were not responsible for sending the initial threatening emails.

The video purporting to show a live attack against a voter database was very likely staged.

The voter data contained in that video appears to be legitimate, but could have been obtained in a variety of ways.

The implication from the video — that there is widespread voter fraud powered by stolen voting data — is false.

Our team noticed a mistake in redaction in the video and reported this to the authorities. This mistake has led to the discovery of a large number of potential other systems used by this actor.

We cannot provide independent attribution to the Islamic Republic of Iran.

This incident raises important issues about the practices of states around voter rolls, particularly Alaska.

This campaign is intended to decrease voter confidence in U.S. electoral processes. There is no evidence of the wide-scale compromise or fraud that these actors claim to show.

The Proud Boys email incident

On Tuesday, October 20th, news broke of threatening emails sent to voters purportedly from the Proud Boys, an SPLC designated hate group. The body of the message included language telling registered Democrats to “vote for Trump or else”. These emails included the legal name of the recipient and, in some cases, their physical address.

An email obtained by Alaska Public Media threatening voters to “vote for Trump or else”

The Proud Boys were quick to deny involvement in these emails. Public reporting surfaced that the emails appeared to be using a spoofed email address, providing early evidence that these emails were not legitimate.

EIP obtained several emails that were sent to voters in Florida, including from our partners at the NAACP. Consistent with research by ProofPoint, we assessed that the emails appeared to originate from two compromised systems, one belonging to an Estonian textbook publisher’s website and the other belonging to a Saudi Arabian insurance company.

One email obtained by EIP was sent via a PHP script belonging to the cpanel suite of utilities on the Saudi Arabian host. This script inserted a header into the resultant email that included the IP address of the calling system. This IP address matches the address from ProofPoint’s analysis. The address, 195.181.170.244, belongs to Datacamp Limited but, per PassiveTotal data, is used as an exit node by Private Internet Access, a prominent VPN service.

An email obtained by EIP appears to have been sent via a compromised host in Saudi Arabia, from a user utilizing a VPN

Analyzing the “Proud Boys” video

Several of the spoofed Proud Boys emails included a link to a video claiming to be from the Proud Boys, supposedly showing hacking of voter information. The video was hosted on OrangeDox, a file hosting website, and was removed by the hosting provider shortly after being shared. VICE News has since published a redacted version of the video (to protect individuals’ personal information).

An email obtained by ProofPoint links to a video claiming to be from the Proud Boys

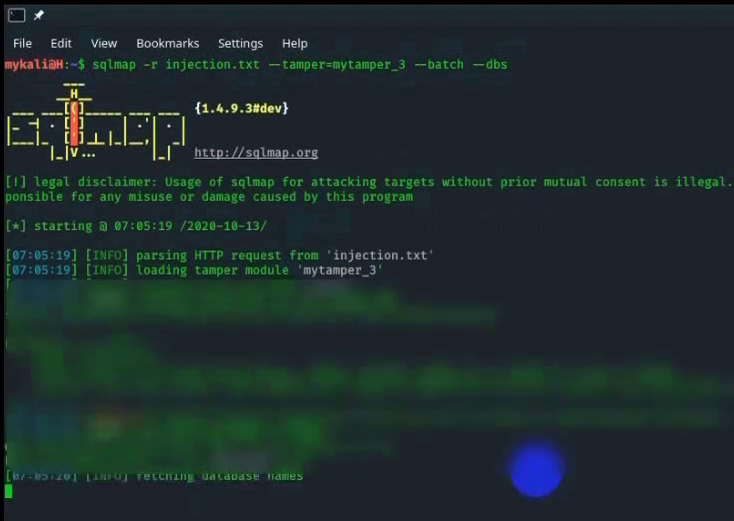

Based on EIP analysis, the video does not appear to show direct targeting of U.S. voting infrastructure, as the email claims. Rather, the video appears to be targeting a host located in Moldova. The actors used sqlmap, a common tool to exploit SQL injection vulnerabilities, in order to exfiltrate data from a database hosted on the Moldovan server. Notably, the database appears to contain one table for each state, indicating that the database contains aggregated voter information and is not an election-related server itself.

Analysis of sqlmap usage

At the start of the sqlmap run, we can see a few things:

The (supposed) local time on the system when the scan was started, 07:05:19 2020-10-13

A text copy of an HTTP request is provided with the -r parameter

A custom “tamper” script is being used, which gives instructions for how to process data before inserting an injection

A screenshot from the video showing sqlmap configuration

10 seconds in, three frames briefly show the payload being used:

This is a standard SQL error-based payload used by sqlmap. This is an in-band method of SQL injection that relies on a web application reporting SQL query errors to users, something that the developer of the web application or framework needs to opt in to and a very poor practice for a production website. In one frame 28 seconds into the video, an IP address (185.183.32.177) is visible unredacted in the sqlmap output. By default, sqlmap writes its output to a directory named after the host it’s executing against — thus, it is likely that this host, located in Moldova, was the server targeted by sqlmap.

The Election Integrity Partnership notified our partners at the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) of this exposed IP address on Wednesday afternoon, although we expect that multiple analysts caught this mistake. Reuters has since confirmed that the exposure of this IP address was one of the factors that contributed to the rapid attribution of Iran.

The IP being targeted is located in Moldova, and owned by WorldStream B.V. The host is a Windows machine running a MariaDB server, with remote management services exposed. It does not appear to run any standard website and has no associated domain names, but runs an Apache web server with an expired self-signed certificate on the non-standard TCP port 444:

Apache/2.4.46 (Win64) OpenSSL/1.1.1g PHP/7.2.33 Server at 185.183.32.177 Port 444The web server returns no content other than the string “123”. Its certificate, as identified by its SHA1 hash, is associated with a large number of hosts on the internet that show obvious signs of compromise, and has been listed as an indicator of compromise by multiple sources, including the Abuse.ch SSL Blacklist. This may indicate that it’s commonly used by a particular threat actor, or is frequently installed as a default certificate.

There are several indications from the video and the related infrastructure that indicate this video does not depict an actual attack being pulled off in the wild:

The target host appears to be serving no obvious production function

The web server appears to be a minimally configured throwaway host

The extreme speed at which results are returned (exploiting SQL injection is very rarely instantaneous)

The web service being explicitly configured to generously report SQL errors via PHP mysql_error()

The improbability of a random IP in Moldova having a copy of voter records of all US jurisdictions, subsequently being discovered and attacked by a third party

Given the above, we speculate that data obtained via another method was stored on a database server running an intentionally misconfigured, bare-bones web application to simulate the appearance of hacking US election infrastructure en masse.

Analysis of voter data shown

The video claims to show voter data for two states, Alaska and Florida

The Florida data shown in the video contains voter ID numbers, addresses, names, dates of birth, and party affiliation. All of this voter data is available upon request from the state Division of Elections.

Voter data from Alaska shown in the video contains several data fields not released publicly by the state, such as the last 4 digits of social security numbers, birth dates, email addresses, and phone numbers. EIP researchers validated several email addresses, phone numbers, and birth dates present in the video using L2 data and other open source resources. EIP did not attempt validating the last 4 digits of social security numbers. VICE news spoke with several individuals listed in the video, who confirmed that their information was valid.

Releasing voter information and claiming it was hacked, as the newly-released video does, is not a new tactic. Early last month, for example, claims spread by Russian media outlet Kommersant reported that Michigan’s voter data was posted on a Russian hacking forum. EIP researchers verified that the data available for download matched Michigan’s public records, and state officials confirmed that the voter data is publicly available to anyone through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Similar claims circulated recently with voter data from Florida being posted on a Russian hacking forum. Again, EIP verified that the data schema matched what is made public by the state.

At this time, it is inconclusive where the Alaska data originated from. Certain vendors, such as L2 Political, sell “appended” voter lists with data such as “voter/customer information”, email addresses, and phone numbers. That said, we would not expect to see partial social security numbers on these lists. If the social security numbers in the screenshot are indeed real, it is possible that the threat actors collected partial social security numbers from the small number of voters displayed in the video based on data from previous breaches in order to give an impression of a breach of voter data. The Equifax breach, for instance, exposed social security numbers of nearly half of all Americans according to an indictment from the Department of Justice. Though unlikely, we cannot rule out the possibility that the Alaska statewide voter registration database was breached.

Analysis of claims of vote fraud

After showing the staged use of sqlmap, the final two minutes of the video are dedicated to creating the impression that the putative Proud Boys hacker is involved in a massive mail-in voting fraud scheme. This invented scheme relies upon the use of a service provided by the Federal Voting Assistance Program (FVAP) of the United States Department of Defense. FVAP provides a service known as the Federal Write-In Absentee Ballot (FWAB) as a backup solution for members of the military, their families and other overseas Americans to vote by filling out an online form, printing it, and mailing the physical ballot.

The “hacker” fills out an FWAB using information from the Alaska voting rolls.

As CISA documented, the FWAB process requires voters to match multiple registration requirements and to physically be overseas, and only 23,291 such ballots were received across the entire United States in 2016. Requesting such a ballot requires the last four digits of the voter’s Social Security Number or a state ID, making such a request possible using the Alaska dataset displayed (if the social security numbers are indeed valid), but not using other voting files that omit such data. Regardless of whether an FWAB can be generated and printed, detecting fraud committed by FWAB would be trivial, due to the multiple requirements, physical mailing of a signed ballot, and rarity of its use.

As Prof. Charles Stewart III of MIT puts it in an interview with EIP, “Rigging an election through FWABs makes no sense on many dimensions. It’s like trying to break into a bank with a butter knife.”

The video shows folders for 40 different states at the end of the video. Notably, the excluded states, with the exception of Alabama, are the 9 states that do not offer online voter registration

The conclusion of the video shows the “hacker” scrolling through folders labeled with the names of 40 states, each filled with hundreds of purported PDF ballots. However, the hacker then fails to open any ballots except those belonging to voters in Alaska. This section of the video is a ruse meant to imply the ability to generate FWAB ballots across the United States. While it is possible to create FWAB ballots using the Alaska data in the video, these other ballots are almost certainly copies lacking real voter information. The Alaska ballots, if legitimate, would need to be printed, signed, and mailed in an operation that would be easy for the state to spot, especially given that fewer than 600 FWAB ballots were returned in Alaska in 2016.

Conclusion

This series of events represents an active measures campaign intended to create the perception of a massive vulnerability in the US election system that does not exist, and possibly to drive tension in the United States through the invocation of a well-known hate group. Every conclusion that the creators of these emails and video wanted Americans to leave with are false:

These intimidating emails were not sent by the Proud Boys

Voting continues to be private, safe and secure, and there is no mechanism by which an outside actor can determine the vote of an individual and later threaten them

The video does not portray a SQL injection attack against the Alaskan or Floridian voter registration systems

There is no widespread conspiracy to change election outcomes via the FWAB system

Such a conspiracy could not succeed

The people behind this campaign were effective, however, in drawing attention to themselves and to their capability to create disinformation. The rapid reaction of government and civil society to these incidents has blunted the capability of these actors to spread their false claims. Our hope is, now that the video and emails have been thoroughly debunked, that media coverage of this disinformation is measured and that future attempts to imply hacking of the voting system are not given unearned amplification or credence.

UPDATE: This post was updated to remove analysis of a TLS certificate that is disputed by other data sources and to change a link to Florida’s voter data files.