Misleading Ads Highlight Loopholes in Google’s Policies

Author: Daniel Bush, Stanford Internet Observatory

Research: Kate Starbird & Himanshu Zade, University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public

On September 7, EIP analysts noticed a certain ad that appeared for Google Search users in the Midwest. The ad, which reads “MIT Election Lab says mail-in voter fraud ‘more frequent’ than…” directed users to a Washington Times article, along with four other Washington Times pages.

The Washington Times ad that appeared on Google Search on September 8, 2020.

The ad drew our analysts’ attention because it seemed to misrepresent the findings of the MIT publication it referred to, which states that “even many scholars who argue that fraud is generally rare agree that fraud with VBM [voting by mail] voting seems to be more frequent than with in-person voting.” In fact this ad — and the headline on which it was based — went somewhat further than mere elision, since the article’s description of the MIT Election Lab’s findings was hidden beneath a “Read More” panel. Readers would have to do some digging before they found that the MIT Election Lab’s framing of the issue was substantially different from that of the headline they had clicked on.

Further investigation showed that this ad was part of a larger campaign apparently intended to undermine voters’ confidence in voting by mail and to direct Google Search users to the Washington Times website. There were five other, similar ads that appeared in different localities around the U.S., including some battleground states, in response to search terms like “electoral fraud,” “mail-in voting,” and “voter fraud.” These ads featured such headlines as:

“No, voter fraud isn’t a myth: 10 cases where it’s all too real”

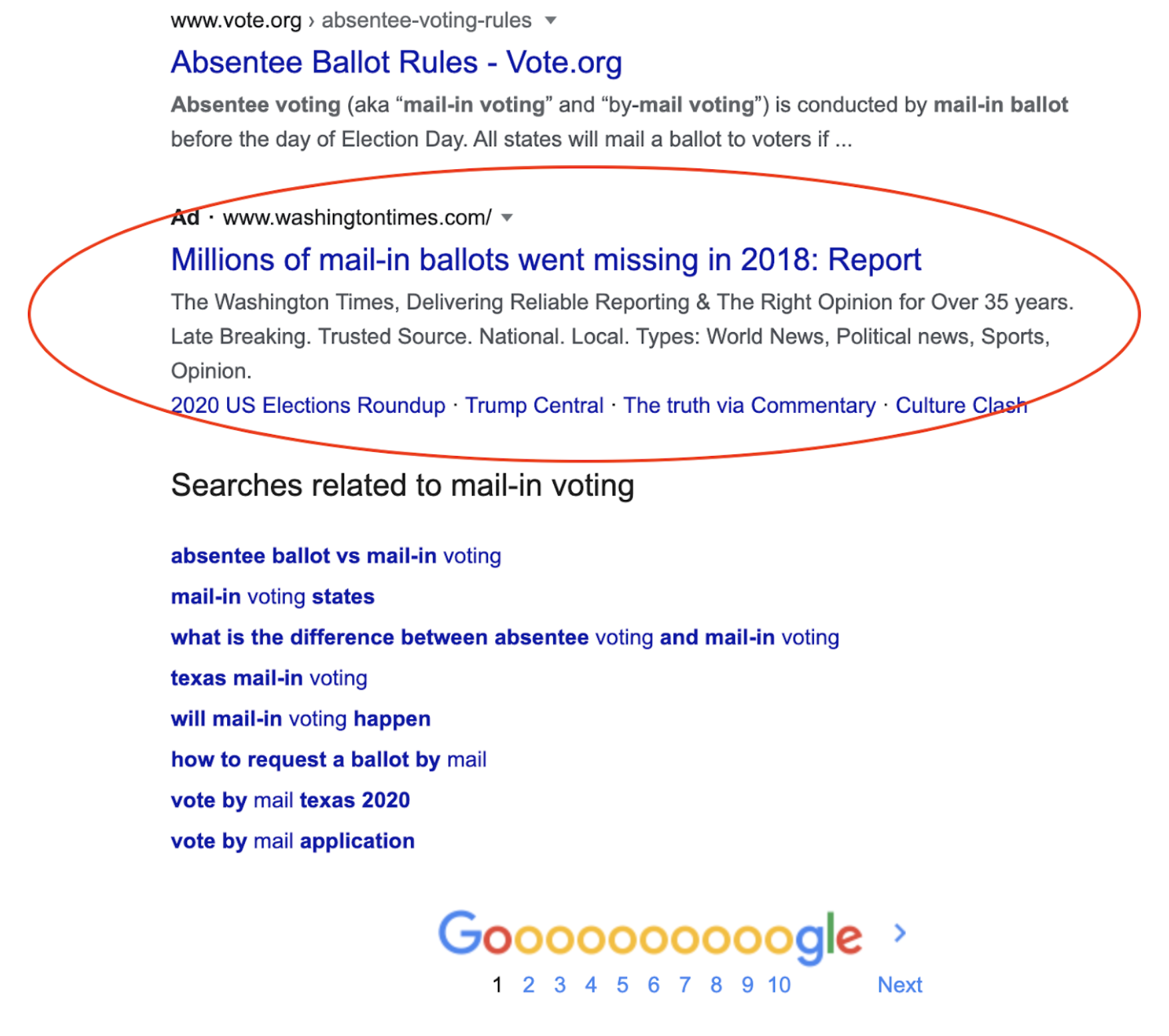

“Millions of mail-in ballots went missing in 2018: Report”

“Unraveling the problems with mail-in voting - Washington Times”

“Donald Trump: Mail-in voting ‘corrupt’ - Washington Times”

“Election fraud is no myth - Washington Times”

A misleading Washington Times ad running in the results of a Google search for “mail-in voting”.

Although we have tracked these ads from early August, when they came to our attention, to the time of writing, it is unlikely that the details given here present the full scope of this ad campaign. Unlike typical political advertising, Google exempts “ads run by news organizations to promote their coverage of federal election campaigns, candidates, or current elected federal officeholders” from its policies on political content. As a result, these ads do not appear in Google’s Transparency Report, and EIP analysts studied this campaign using other forensic methods.

This situation reveals two problems with the way Google handles political ads of this kind. First, it shows that advertisers are using misleading clickbait headlines to put partisan political content in front of users. Several of Google’s ad policies would seem to apply in this case and require that the ad more accurately represent the content it is advertising.

The second problem is that Google’s transparency policy allows ad campaigns that are tied in some way to media organizations to circumvent its transparency policies. The primary intention of the ads described above seems to be to undermine voters’ confidence in voting by mail, and if the same ads were paid for by a Super PAC, Google would require that certain facts about the campaign be made public: who paid for the ads, how much they spent, and who they targeted. As things stand, the Washington Times ads are opaque to outside observers — in fact, there is no way to be certain that it is actually the Washington Times that is paying for the ads. The tactics used by the Washington Times ads in this case are similar to those of the Epoch Times, which made headlines for using ads that evade transparency rules and spam users with partisan content.

Google could fix this problem by making two changes to its policies:

Enforce its prohibition on clickbait ads and unreliable claims when it comes to political advertising. Since the advertisers pay for the words that appear in the ads, these words should have some reasonable connection to the underlying content they are advertising.

Repeal its policy exempting media outlets from its transparency report. Currently, an organization that deems itself “media” can evade reporting requirements, a loophole that is being used to spread partisan content without accountability. Repealing this exemption would bring Google’s policies in line with those of Facebook and Twitter and mitigate advertisers’ ability to manipulate ad services in this way.