Laying the Groundwork: Meta-Narratives and Delegitimization Over Time

Authors: Renee Diresta, Isabella Garcia-Camargo, Stanford Internet Observatory.

Contributors: Kate Starbird, Morgan Wack, University of Washington Center for an Informed Public. Vanessa Molter, Graphika.

The 2020 election will be different from any other electoral process in U.S. history. Not because of the likelihood that the country won't know who won on election night — that’s happened before — but because for the first time, powerful American politicians and partisan media influencers are attempting to preemptively delegitimize the validity of the election itself.

This election is taking place in challenging times: An ongoing pandemic means that tens of millions of Americans will vote by mail. Some state election results may not be available until days after November 3rd. Ongoing protests have exacerbated tensions, and widened partisan divides. The combination of unprecedented circumstances and social unrest has contributed to an increase in conspiracy theories and partisan accusations of dirty dealing from both bottom-up grassroots social media chatter and top-down elite communications.

One narrative in particular has emerged that links social protests and voting-related accusations, and in doing so, attempts to preemptively delegitimize the 2020 election: the claim that the United States is in the midst of a “color revolution,” a Deep State coup to steal or disrupt the re-election of the President of the United States. This narrative is worth examining not for its content, but to understand how it weaves together a wide swath of discrete events into an overarching meta-narrative, involving both influencers and ordinary users in the process. The meta-narrative becomes a scaffolding on which any future event can be hung: any new protest, or newly-discovered discarded ballot, is processed as further confirmatory evidence that a color revolution coup is indeed underway, that there is a vast conspiracy to steal the election, and that the results will be illegitimate. What may previously have been isolated incidents with minimal social media traction may gain significant new weight when they are processed as additional evidence of an underlying conspiracy.

These meta-narratives provide a long-term cohesive ideological unit through which a community can interpret events. They are distinct from simple delegitimizing content — a story of some ballots found in a ditch, a doctored video of voter fraud — which can quickly be fact-checked as individual incidents. Their long-term nature makes them particularly challenging to respond to, as they are laying the groundwork to delegitimize a future event, setting the stage to have a claim to point back to if events play out in a certain way. We present the example of the “color revolution” claim as a case study in propagation tactics, reach, and potential broader adoption of meta-narratives.

Summary of Color Revolution Activity

The term “color revolution” was coined in the late 20th century to describe revolutions in which repressive regimes tried to hold on to power after losing an election, spurring domestic, often student-led popular protests for democratic change. However, in 2005, autocrats in China and Russia began to redefine the term away from its domestic-activism origins, using it instead to imply externally-imposed regime change — in particular, regime change designed to look like a popular uprising while being furtively orchestrated by intelligence services from Western democracies. Today, the term is being applied to American politics in a somewhat unexpected way: prominent conservative influencers have begun to suggest that the U.S. is experiencing a Deep State-backed color revolution intended to steal the election from President Trump. This narrative works to pre-emptively delegitimize election results unfavorable to the president via unfounded claims — including those surrounding ballots — and is thus in scope for EIP.

The propagation of the narrative has occurred over several months, waxing and waning in popularity, but gaining gradual adoption as a frame upon which other events are communicated

August 2019 - August 2020: Introducing the Narrative. Early spread and introduction of the idea. International coverage by RT (Russia’s state-controlled media) and others in op-eds.

August 2020 - September 16th 2020: Mainstreaming. First major push to introduce mainstream audiences to the narrative, first by former Trump speechwriter and prominent conservative commentator Darren Beattie, which leveraged both social and mainstream media.

September 17th - October 7th: ‘Super Spreaders’. Early propagators employ group ‘super spreader’ dynamics, in which the active user spreads the same content into dozens of Groups simultaneously, to gain traction. They are joined by Glenn Beck, political pundit and conspiracy theorist, and other influential, verified conservative influencers who use the term more liberally to push normalization.

October 7th - Present: Normalization. An October 7th “Q-drop” (a post from the actor that goes by “Q” in the QAnon conspiracy theory community) pushes the term into a large, aligned new audience: the cluster of online communities dedicated to following Q, which has previously spent years suggesting that the President is battling Deep State forces. Group super spreader dynamic continues, but the term now enters the casual vernacular of a broader right-wing audience.

Evidence of the domestic spread of this narrative can be found as early as December 2019. However, state-controlled media such as RT (Nebojsa Malic) and aligned publications (Oriental Review, Strategic Culture) began to advance the Color Revolution theory as far back as August 2019, and again when the George Floyd protests erupted in June.

RT op-eds and articles speculating about a color revolution in the US began to appear as early as August 2019.

The theory was mainstreamed by Darren Beattie beginning in early August 2020. Darren Beattie appears to have begun a public roadshow to promote the theory beginning with a public discussion with Steve Bannon on August 11th. Revolver.News, a far-right outlet, then began a detailed series on the color revolution after Beattie’s first appearance with Bannon, on August 16th. The Revolver.News series on color revolution seems to be the most detailed coverage of the theory, and it garners engagement with each new post expounding on the topic. Right-wing influencers Adam Townsed and Michelle Malkin subsequently hosted Beattie on their shows on August 18th and September 3rd, respectively.

On September 15th, Beattie appeared on Tucker Carlson, a segment that significantly drove up social media commentary on the color revolution claim. Glenn Beck and other right-wing influencers subsequently picked up the narrative more intensely, creating their own programming about it and hosting Beattie on their shows. Between August and mid-October 2020, the term was used to contextualize mail-in voting incidents and general social unrest in the US by several major conservative influencers, including Glenn Beck, Michelle Malkin, Miranda Devine, Faith Goldy, and Jack Posobiec.

Darren Beattie’s debut on Tucker Carlson, above, drove up public awareness of the color revolution thesis. Graph from CrowdTangle.

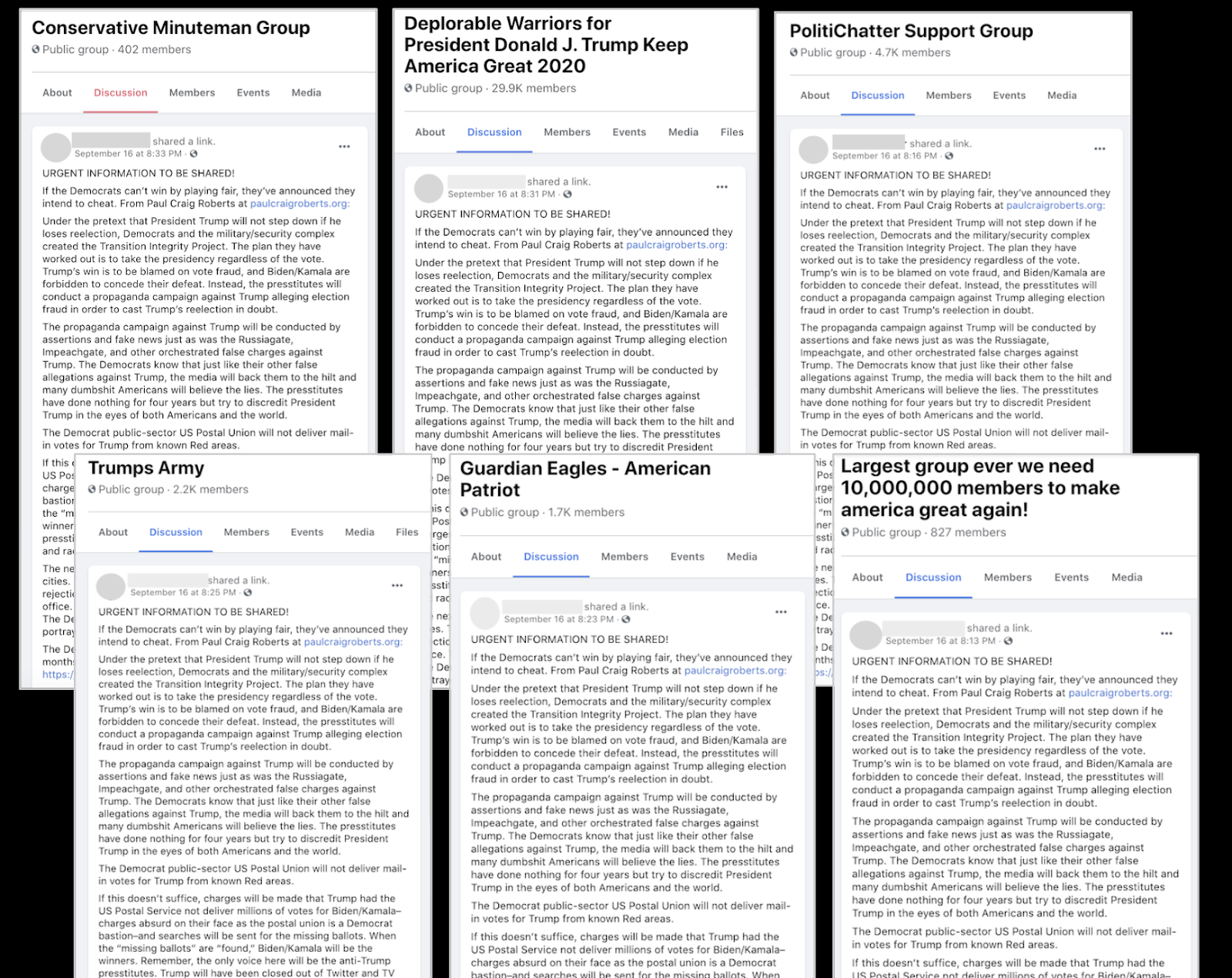

After this “mainstreaming” portion led by prominent partisan influencers, social media users who found the story appealing moved the narrative into Facebook groups and pages through shares. Some displayed “super spreader” behavior, in which an extremely active user shares content into dozens of different Groups nearly simultaneously. In this specific case, users shared links either directly related to blog or news coverage of the color revolution claims themselves, or used the phrase “color revolution” in their commentary while sharing links to stories of other incidents they seemed to believe were evidence of the claim. On several occasions, individuals pushed color revolution content into between 5-15 distinct Facebook groups at a time, enabling it to reach tens of thousands of group members. One notable example was the sharing behavior around a recent article from The Hill about the Democratic Party concern that votes tallied after election Night might contradict what will at first look like an early re-election win. This article achieved minimal spread in several left-leaning Facebook groups between its publication September 7th through September 9th. Then on September 16th, it was posted by a super-spreader user into a popular Rush Limbaugh FB Group with over 65K followers, with the claim “URGENT INFORMATION TO BE SHARED! … The Democrats have been gaming their planned election theft for months, and the public is being prepared for it”. The post went on to call out Americans it claimed “continue to sit sucking their thumbs while Democrats pull off a color revolution and overthrow an elected president.” Following this, the user shared the link with the color revolution framing to at least 10 additional public groups.

An example of a ‘super spreader’ posting dynamic from an individual who posted this exact message in at least 10 public groups within a 20 min time period on September 16th.

The combination of mainstreaming efforts by conservative influencers and adoption and propagation by Facebook users has pushed the color revolution frame into a broader portion of the right-wing social media ecosystem. A quick search on Twitter for the term turns up hundreds of casual uses of the term each day; CrowdTangle data indicates the same is true on Facebook. As of October 13th, color revolution narrative activity is not increasing but instead seems to have become a low-grade background chatter with occasional spikes of usage activity when prominent influencers renew their use of the term.

Twitter activity for the term ‘color revolution’ per day over a week-long period. The narrative experienced another low-grade spike with the publishing of another Revolver.News piece on the matter.

Jack Posobiec, an alt-right political activist and correspondent for One American News Network, promotes the color revolution framing

Potential Effects

Stories imputing a rigged election certainly exist outside of the framework of the color revolution; EIP has covered many in our work to date. However, narratives serve as organizing structures and lenses through which to view events, and cohesive ideological frames like the color revolution are built slowly over time. The broad claim that a color revolution is underway, with nefarious actors purportedly funding protests and destroying ballots, provides a convenient way for those seeking to delegitimize the election to connect unconnected events and to create a compelling villain while doing so. This is in many ways similar to the long-running narrative of a Deep State actively and deliberately undermining the presidency — an unsubstantiated claim repeated over time that gradually came to offer a robust framework and associated vocabulary to purportedly explain a variety of events.

By promoting the color revolution narrative, conservative influencers appear to be priming their audience to read all future events around the election as potentially part of that revolution. Previous isolated instances of “mail dumping” are recast as evidence that mass voter fraud is underway, with the imputation that the instances that make the news are only the tip of the iceberg. As experts predict a “blue shift” in the days following Election Day as Democratic-leaning mail-in ballots are counted — a process that could potentially last weeks — audiences who have heard that the election is being stolen will likely react with deep suspicion and possibly outrage, as the “theft” that they have primed to believe is coming, appears to actually occur.

Recommendations

The challenging issue with delegitimization frameworks such as the color revolution narrative is that it's a broad interpretation of events, unwieldy for a platform factcheck. It’s a long-term conspiratorial explanation, not a single viral misinformation incident. This makes it all the more difficult for platforms to respond: any one post or piece of content may receive negligible engagement, however, the accumulation of these references is what matters.

Research indicates that conspiracy theories generally aren't as viral as other rumors... they take longer to develop and they sustain over time, periodically gaining momentum when a new event or piece of evidence can be leveraged to push them forward. Besides the one large push into mainstream broadcast media in mid-September, in which Beattie himself estimated that 5 million people saw his Tucker Carlson segment, the color revolution has not had a significant single ‘viral’ movement on social media. Rather, there are small “spikes” at various points over the two month period between August and the present as the narrative is leveraged to interpret other events.

A recent example of color revolution being leveraged by an ordinary user to explain the most recent actions of YouTube against QAnon on their platform. This also is consistent with the incorporation of the color revolution narrative into the omniconspiracy QAnon after the terminology was used in an October 7th Q-drop.

In aggregate, narratives such as this lay strong groundwork for delegitimizing election results — which is against platform policies. However, they are not suited to policy interventions such as takedowns or even informational interstitials. As such, we would suggest two approaches:

Media Awareness. As with the “Deep State” narrative, networked narratives around election delegitimization are most dangerous when they are amplified through traditional media channels. Such amplification is often made possible because reporters and prominent media influencers are not aware of the provenance of the terminology or the underlying conspiracy theories associated with specific terms. At minimum, reporters and other influencers should be made aware of the emerging meta-narratives and the attempts to mainstream them, and take care to not unwittingly expose their readers or viewers to it without contextualization.

Inoculation. When delegitimization narratives reach a certain level of spread, inoculating the public against them may be the only viable way forward. Inoculation approaches involve making the public aware of the provenance of the concept, its role in disinformation campaigns, and alerting people to the various forms they might expect to see. Inoculation efforts must be approached with care, as there may be at times a fine line between preempting a narrative, and unwittingly contributing to early amplification.

At minimum, researchers and civil society organizations with ties to targeted communities should understand these now common dynamics: blue-check amplification and super spreader reposts of unique emergent phrasing, YouTube interview and podcast “roadshows” to further socialize the idea, and additional factors which signal attempts to establish a new narrative. Overall, awareness of these narratives, when handled with care, can be an important first step to dismantling the power they are quickly accumulating.