Examining Twitter’s policy against election-related misinformation in action

Authors:

Kate Starbird, University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public • Carly Miller, Stanford Internet Observatory

Contributors:

Paul Lockaby and Michael Grass, University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public

Elena Cryst, Stanford Internet Observatory

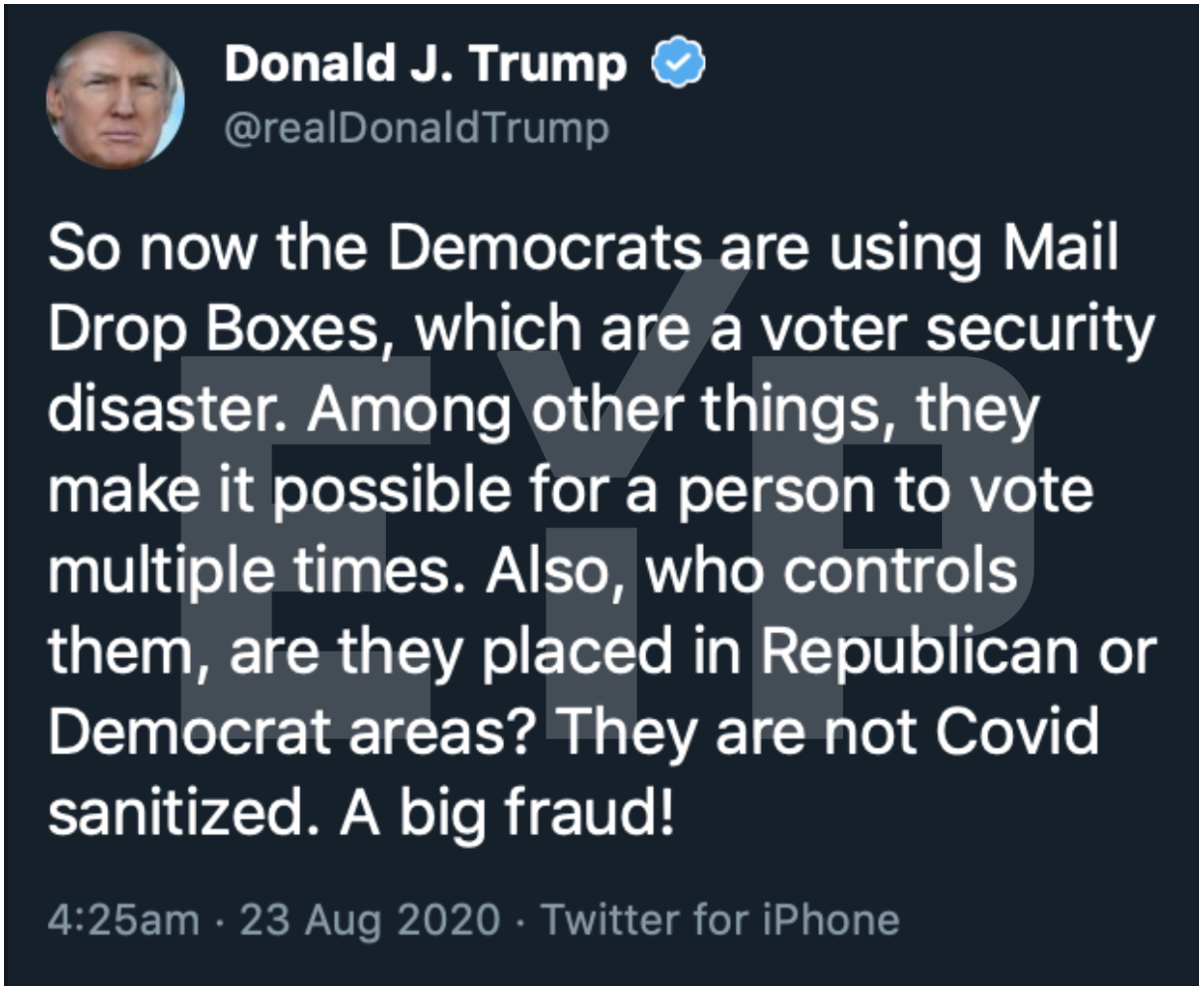

On Sunday morning, Aug. 23, 2020, President Trump posted a tweet (through his @realDonaldTrump account) that contained misleading information about mail-in voting and ballot drop-off boxes. Ballot drop boxes have been used for years in some states without any issues. Washington state’s top election official, Republican Secretary of State Kim Wyman, for example, has stated that she knows of no incidents of tampering or fraud connected to ballot drop boxes. The claims in the tweet violated Twitter’s relatively new Civic integrity policy, which addresses misleading information about how to participate in the election, including content that functions to suppress and intimidate voters. And so, on the day before the Republican National Convention, the social media platform was once again faced with deciding how to respond to misleading election-related content from the president of the United States.

Figure 1: A screenshot of Trump’s tweet posted August 23, 2020 at 4:25am PT (7:25am ET).

Interfering with an election — or using false or misleading narratives to undermine trust in the results — is a threat to democracy. Social media platforms, including Twitter, are increasingly developing policies and taking action against violations — even on content shared by prominent elected officials, such as President Trump. However, as we’ve noted in a previous post, while social media platforms have policies in place to address false and misleading content meant to interfere with election procedures, participation, or results, there is significant variability in how and when such policies are applied.

In this data-driven post we first examine the tweet’s propagation through Twitter and the effect of the platform’s response — in this case, adding a label and disabling the ability to retweet the content. We then discuss how the elements of Trump’s tweets violated Twitter’s policies and break the tweet down against 4 key categories of election integrity.

Key Takeaways:

Twitter disabling retweets on President Trump’s tweet had a clear effect on its propagation. Our analysis shows that their action abruptly stopped the spread of the tweet through retweets.

However, our data also reveal that once the retweet function was disabled, Trump’s supporters shifted from simply retweeting to quoting (retweeting-with-comment). This suggests that problematic information will continue to spread via that mechanism after the retweet button is disabled.

The sentiment of quote tweets before and after Twitter disabled the retweet function shifted significantly: Quote tweets prior to Twitter’s action were largely critical of his tweet (and encouraging Twitter to take action), while quote tweets after Twitter took action overwhelmingly voiced support of the president’s original tweet (and criticized Twitter for taking action). This provides a window into some of the partisan discourse around when, whether, and how the platforms apply their policies on problematic information.

Platforms must act swiftly to enforce their policies. The majority of this problematic tweet’s spread had likely already occurred by the time Twitter took action to dampen its spread. This suggests the company needs to move much faster to apply their policies if they want to make an impact on the spread of election-related mis- and disinformation.

Caveats:

This account focuses on Twitter because that platform allows access to their data through public APIs, enabling our analysis.

Additionally, Twitter was the only platform to take action against Trump’s Aug. 23 post. Though the same content appeared on President Trump’s account on Facebook, Facebook did not take any additional action to address it other than apply a link to Facebook’s Voter Information Center, something the platform says it applies to all posts on voting in the US and Facebook.

Twitter’s Action

A few hours after Trump’s tweet, Twitter took action, per its Civic integrity policy, to address the election-related misinformation it contained.

In most browsers, the tweet text was replaced by a warning notice, which appeared as the following:

Figure 2: A screenshot of what Trump’s tweet looks like on most browsers. Some Twitter clients such as TweetDeck displayed the tweet without the notice. More detail on this discrepancy can be found here. When users click “view” the original text appears while the notice is still visible so the user knows the tweet’s content violates Twitter’s policy.

The notice links to Twitter’s policy about public-interest exceptions; while the tweet violated their Civic integrity policy and may otherwise have been taken down, the platform decided not to remove the tweet because of compelling public interest in allowing users to see content from an elected official.

Twitter also took additional action to reduce the spread of the tweet: it disabled retweets and likes, but continued to allow quote tweets (retweets with comment). The platform also posted a quote tweet of the offending content in order to clarify that the tweet would remain on the service given Twitter’s public-interest exception.

To better understand how Twitter’s policy-driven actions affected this tweet’s propagation through Twitter, our partners at the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public tracked the spread of Trump’s tweet before and after Twitter applied its notice.

How This Action Affected the Spread of Trump’s Tweet

A Little Bit About Our Data

The data that informed this research was collected from Twitter in real-time using their public APIs. We track a number of election-related terms, including three terms that appear in Trump’s August tweet: “vote,” “voter,” and “fraud.” Due to rate limits, we do not always catch every tweet. But we do have methods of estimating how much data we are losing at a given time. In this case, our collection captured Trump’s original tweet and a large percentage of its retweets (93.4%).

In total, between the time it was tweeted and the time of this analysis (Aug. 25 1:15 UTC) our data include:

24,721 retweets of the original Trump tweet,

13,754 quote tweets (retweets with comment) of the original tweet, and

72,779 retweets of the quote tweets of the original tweet.

Our analysis below breaks down each of these different vectors in the three graphs below.

What Happened When Twitter Disabled the Retweet Button?

Trump’s original tweet was retweeted (using the retweet button) a total of 24,721 times. Below is a temporal graph that shows the number of retweets per minute (black).

Figure 3: The graph of retweets begins with Trump’s post at 11:25 UTC. The vertical dotted line represents the time in which Twitter’s action went into effect. The analysis of Trump’s tweets are done in Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which is 4 hours ahead of Eastern Time and 7 hours ahead of Pacific Time.

The tweet rate quickly spiked to a peak of nearly 350 tweets per minute, and then began, quite rapidly, to decline. The shape of that decline, what looks like exponential decay, is relatively typical of highly retweeted tweets. Within about an hour, the tweet had fallen to about 100 tweets per minute. The tweet rate continues to decline for another six and a half hours before abruptly falling, permanently, to zero tweets per minute. We can assume from this graph that Twitter’s action to dampen the spread of the tweet (disabling the retweet button) went into effect at 16:42 UTC (12:42 p.m. ET and 9:42 a.m. PT), at the time of that precipitous drop in our graph, and more than five hours after the rule-breaking tweet was originally posted.

Retweets Seem to be Replaced by Retweets with Comment

Twitter’s action to remove the ability to retweet clearly had an effect on the tweet’s propagation. However, their policy action does not include quote tweets (retweets-with-comment). As their tweet describing their policy states, and the graph shows, Twitter allowed those to continue. Below, we have added quote tweets-per-minute to the graph (in blue).

Figure 4: The graph above displays the volume per-minute of retweets (Black) and quote tweets (Blue) of Trump’s tweet. The number of quote tweets spikes at the time Twitter took action and removed the ability to retweet (represented by the vertical dotted line). The line of quote tweets then decreases in what seems to be alignment with the original but no longer continuing retweet graph.

This graph shows that quote tweets of Trump’s disinformation tweet remained pretty steady, around 20 tweets per minute, for several hours after his original tweet. During this period before Twitter took action, the content of these quote tweets (retweets-with-comment) was primarily critical of Trump’s tweet. For example:

Figure 5: a quote tweet critical of Trump’s original tweet.

This graph also reveals that as the retweets were dropping to zero, the number of quote tweets jumped from about 15 per minute to about 35 per minute. The shape of the graph seems to align almost perfectly with the early retweet graph, suggesting that some people who would have previously retweeted the tweet chose to quote it (retweet-with-comment) instead.

Indeed, taking a closer look at the quote tweets that occur right after Twitter disabled the retweet button, we can see a surge in quote tweets echoing the original sentiment of Trump’s tweet, as well as some quote tweets accusing Twitter of unfairly censoring Trump’s tweet. For example:

Figure 6: a quote tweet accusing Twitter of censorship.

An analysis of 50 random tweets shows that these supportive tweets constitute a large portion of the quote tweets after the surge. This is a stark contrast to the quote tweets prior to the surge (examined through a similar random sample), which were mostly critical of Trump’s original tweet.

Retweets of Quote Tweets

Looking at retweets of quote tweets provides another perspective on the spread of this tweet. Trump’s tweet was quoted 13,754 times and those quote tweets received a total of 72,779 retweets. In other words, his misleading tweet spread further via quote tweets than via simple retweets. This is true even BEFORE Twitter took action to disable the retweet button.

Below, we’ve added the tweet rate for retweets of quote tweets (in red). [I know, it sounds convoluted, but stick with me.]

Figure 7: The graph above displays the volume per-minute of retweets (Black), quote tweets (Blue), and retweets of quote tweets (Red) of Trump’s tweet. The number of retweets of quote tweets rises steadily for about three hours, and then spikes at 15:14 UTC before falling off sharply. Eventually it falls to about the level of the quote tweets, suggesting a rate of about one retweet per quote tweet.

In contrast to the retweet rate and the quote rate, the rate of retweets of quotes continues to grow for the first three hours after the original tweet was posted. It eventually reached a rate of about 150 tweets per minute prior to spiking to more than 400 tweets per minute.

That large burst (between 15:10 and the moment Twitter took action at 16:42 UTC) consists of 20,785 retweets of several different quotes (retweets-with-comment). Most of those are retweets of quote tweets pointing out the falsehoods in Trump’s original tweet and advocating for Twitter to take action against Trump’s tweet. Several (not just one) of the highly retweeted quote tweets were authored by political pundit George Conway, including this one:

Figure 8: A screenshot of a quote tweet from George Conway, founder of the Lincoln Project, advocated for Twitter to take action on Trump’s tweet.

The tweet rate for those predominantly critical quote tweets falls off rapidly after its peak at 15:14 UTC and even more rapidly — but not completely — after Twitter takes action to disable the retweet button. Interestingly, retweets of quote tweets continue to decline, even when the rate of quote tweets increases (after the retweet button was disabled). It is not clear if Twitter acted internally (within their recommendation algorithms) to reduce the spread of retweets of quotes, or if this was a secondary effect of their other actions (adding the warning label, disabling the tweet button). For example, it is possible that the final rapid drop (and remaining low volume) of quote tweets was due to user reluctance to retweet after the label appeared.

Policy Analysis — Twitter’s Civic integrity policy

Sunday’s tweet was the second time one of the President’s tweets triggered a review under Twitter’s Civic integrity policy. The first occured on May 26, 2020 when Twitter found that President Trump’s tweets about voter mail-in ballots in California “could confuse voters about what they need to do to receive a ballot and participate in the election process.” In that incident, the tweets were fact-checked and labeled, but left up for Twitter users to engage with via comment, like, and retweet. Previously, there have been other election-related tweets from @realDonaldTrump that the platform chose not to act on; one tweet by the president in July, for example, was deemed too broad and non-specific to meet the threshold for Twitter to take action. Each of these cases provide researchers a window into what may be deemed in and out of scope when applying the policies in practice.

Measuring Trump’s Mail Drop Box Tweet Against Twitter’s Policy

Sunday’s ballot drop box tweet levied multiple attacks on election legitimacy and features multiple types of election interference. In a previous blog post, the EIP identified a framework of four key categories of election interference: 1) Procedural Interference, content related to voting procedures; 2) Participation Interference, content related voter intimidation; 3) Fraud, content that encourages or alleges illegal activity related to the election; and 4) Delegitimization of Election Results, content that calls into question the results or overall integrity of the election.

The table below breaks down Trump’s claims across three different dimensions: the category of electoral interference, the policy we believe should apply to the claim, and lastly, whether Twitter took action on that specific statement.

Table 1: Trump’s tweet is analyzed across the EIP’s 4 categories to provide a deeper look into the specific ways the tweet calls the integrity of the election into question. This breakdown also provides insight into how Twitter applied its policies to the claims in the tweet. The highlighted red box is the claim that Twitter took action on as a violation of its policies.

Summary

Trump’s tweet on ballot drop boxes contained misleading information that threatens the integrity of the election, and Twitter took action — in accordance with their existing policies — on his post. Twitter’s transparency provides us with more understanding to why the platform applied its policies and what the deciding factors were. However, from the data we collected, Twitter’s action appears to have been too little, too late. Though we can’t know if the tweet would have experienced a resurgence after Twitter’s action, the temporal graph suggests that most of the tweet’s spread had already occurred; the retweet rate was already low and declining. Additionally, though it’s clear from the graph that the misleading content spread further through quote tweets (and retweets of quote tweets) than through retweets of the original, it’s unclear if the platform took additional steps to dampen the amplification of quote tweets. Our analysis shows that through the actions they took very well could be the right actions (they stopped the spread pretty quickly), Twitter needs to move more quickly if they want the policy to have a real impact on the spread of misleading information that threatens the integrity of the upcoming election.