Election Official Handbook: Preparing for Election Day Misinformation

The Election Integrity Partnership has analyzed roughly 400 cases of election-related dis- and misinformation on social media in the last eight weeks. This memo, written for our partners in the election administration community, is intended to distill the findings and recommendations stemming from this work regarding best practices for the benefit of U.S. election officials. Primarily, election officials must prepare for numerous viral falsehoods around election administration to propagate online on election night, as well as to be ready for these falsehoods to persist for several weeks.

2020 Misinformation Trends

EIP has noted the following trends in the election-related misinformation analyzed to date:

Election-related misinformation has been overwhelmingly domestically sourced and propagated. Partisan networks command significant reach; by contrast, while there have been several cases of alleged foreign interference, the direct impact of these efforts appears minimal.

Cross-platform spread is evident in most cases of election-related misinformation. Although most observed misinformation has been propagated through Facebook and Twitter, content is rarely restricted to one platform. Small platforms often seed election-related misinformation into the wider information environment.

Younger voters use different platforms than older voters and are susceptible to different kinds of misinformation. Election-related misinformation on photo and video-centered platforms popular with younger demographics has contained a high degree of well-intentioned misinformation in which young voters seek to “educate” each other while inadvertently amplifying misleading or unvetted claims.

Common Narratives

EIP has tracked three broad categories related to election-related misinformation. Under each category, we provide the top narratives and an example incident. We’ve included concrete examples pulled from EIP’s encountered content this election cycle in Appendix C.

Content that spreads confusion about voting procedures or technical processes

Impersonation of election officials or spoofing of official online election resources such as official accounts or websites that can seed or amplify falsehoods.

False or misleading content about election deadlines or voting procedures, calls to vote twice, and well-intentioned or malicious misinformation about voting dates.

Content that may result in direct voter suppression

Stories, particularly with images, that depict or claim to depict intimidation at the polls, especially regarding the presence of poll watchers, law enforcement, or protesters.

Accounts of intimidation based on voting preferences, including threatening letters sent to voters on both sides of the aisle.

Unfounded claims which may dissuade voter participation, such as unfounded claims of extremely long lines or abrupt polling location closures.

Content that may delegitimize the election

Claims of widespread voter fraud based on decontextualized, fragmented, or fabricated anecdotes. For example, claims that someone has cast multiple ballots without acknowledging processes to deal with redundancy.

Claims that the USPS, election administrators, or poll workers are acting in bad faith, using images of ‘mail dumping’, or decontextualized videos from poll worker training.

Claims that voting infrastructure is broken or compromised, and particularly allegations about the reliability of voting machines.

Claims of large-scale conspiracies or general partisan collusion by election administrators spun from court rulings or recent legislative changes.

What to Expect: Challenges for Election Day and Beyond

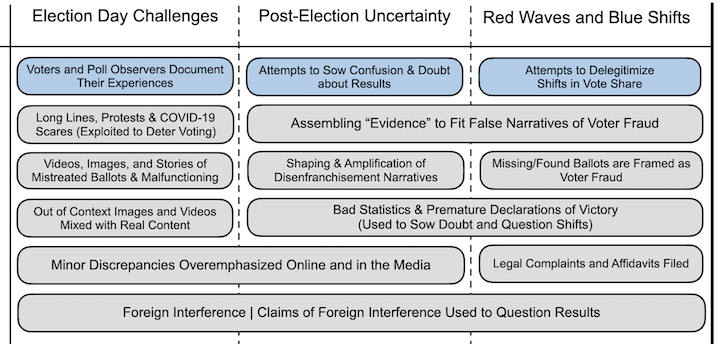

Image from EIP’s full analysis of the information space during the post election period, which includes our recommendations for the general public and media in this time period.

Election Day Challenges

Real-time documentation leads to real-time confusion: Voters will be sharing images, videos, and even live streams from polling locations. This content will receive widespread organic amplification, particularly if it shows long lines or demonstrations.

Expect that this content will be decontextualized and used as the basis for claims of voter disenfranchisement on and after election day.

Expect an overemphasis on discrepancies or minor errors that will go viral and potentially lead to broadcast media inquiries.

Misperception and exaggeration of COVID-19 risks: Viral election-day images and videos will include scenes of maskless individuals or individuals who do not follow social distancing guidelines.

Expect a particular emphasis and steep reputational cost for election officials who are pictured without personal protective equipment, even if they are on a break or otherwise not engaging with the public.

Expect the malicious amplification of such content with the intent of exaggerating COVID-19 risks and scaring voters away from the polls.

Concern about intimidation and potential violence at polls: The American public has been primed to expect violence from actors with a history of street confrontation such as the Proud Boys, Bikers for Trump or antifa. Historically, isolated incidents of voter intimidation have received significant attention in U.S. media (see the highly publicized 2008 Philadelphia incident in which the New Black Panther Party offered election “security.”)

Expect that images and videos of election-day confrontations, protests, or armed security at the polls will see viral spread on social media.

Expect that this content will especially be the target of foreign adversarial media, such as RT and Sputnik.

Post-Election Uncertainty

Premature declarations of victory: Social media has enabled the rise of armchair data scientists and pundits who command significant audiences and who may be incentivized to call races before broadcast media. Delivery of mail-in ballots may distort election-night results.

Expect that unofficial results, while incomplete, may be used by candidates or their supporters to prematurely declare victory.

Expect that such premature declarations of victory will lay the groundwork for contesting supposedly “fraudulent” final results.

Expect that such premature declarations of victory will sow public doubt and uncertainty regarding the official results, should the two diverge.

“Lost ballots” and revitalization of older misinformation narratives: Most modern U.S. elections have been followed by allegations of lost or hidden ballots. These claims are typically unsubstantiated.

Expect that lost ballots will become a widespread and enduring misinformation narrative in the days following the election.

Expect to see lost ballot misinformation “proven” by the revitalization of numerous previous instances of voting-related misinformation. Dormant viral storylines are often repackaged months or even years later.

Expressions of disenfranchisement: There will be viral testimonials on and following election day by voters who feel that they were disenfranchised, either by long election-day lines or by confusion over mail-in voting deadlines.

Expect these testimonials to be amplified by losing candidates and their supporters to cast doubt on the legitimacy of the election.

Expect these testimonials to be heavily amplified by foreign adversarial media to highlight failures in the democratic process.

Recommendations

Establish effective communications channels

Identify trusted journalists or social media influencers who have significant reach in your jurisdiction. Be ready to tag them into your public service announcements and encourage them to amplify with their platforms. Engage with them in advance if possible.

Clarify who in your organization is responsible for issuing tweets or rapid-response statements. Seek to minimize operational barriers that might handicap the speed of your organization’s response to misinformation. Time is often of the essence in effectively countering falsehoods on social media.

Agree on thresholds of response and follow counter narrative best practices.

Avoid feeding amplification, especially for incidents with low traction. Decide on the thresholds for response early, taking into account both the spread and potential risk of the content.

Do not amplify election-related misinformation by retweeting or resharing it directly for the purposes of debunking it. If you must include the false claim in your response, use a screenshot instead, crossed with a red line or watermarked as ‘MISLEADING’.

Do not engage with the creators or spreaders of obvious misinformation. To do so is to raise their visibility and expand their audience.

See Appendix B for counter narrative best practices for further exploration of these tradeoffs.

“Pre-bunk” the most likely election-related misinformation; be proactive

Invest heavily in voter education about potentially confusing election processes through the election, especially if your state voting guidelines have recently changed.

Remind voters of safety precautions being taken for in-person voting, particularly COVID-19 precautions.

Explain to voters early and often that unofficial election results are subject to fluctuations, especially if significant shifts in vote tallies may occur based on your state’s vote-counting process.

Stress that voters should primarily go to you for election information, and that delayed results are not illegitimate results.

Review previously encountered misinformation narratives

If your office has previously issued public service announcements about election-related misinformation, ensure that communications staff are familiar with these announcements and can rapidly re-issue them.

You are likely to see previously discredited storylines reappear on or after election day. Save time by preparing to debunk them again.

See Appendix A for examples of counter narratives produced by EIP and election officials.

Above all, prevent information vacuums

Other actors will take advantage of information vacuums for malicious ends. The best way to prevent this is to fill them with your own communications.

“No news” is still news.

Brief early, brief often, brief consistently until everything is done.

Maintain information-sharing with the appropriate officials at all times

Reporting incidents to the Center for Internet Security (CIS) ensures that all federal stakeholders are aware of the event, and can take appropriate action..

EIP will also conduct analysis on each of these reports to determine virality, cross-platform spread, potential attribution, and EIP will examine all aspects of the event. Relevant findings will be shared with the reporting entity.

Appendix

Appendix A: Counter Narrative Examples

The EIP often produces rapid response Twitter threads to quickly debunk and issue counter narratives for incidents the analyst team has detected in real time. We have linked some of these counter messages below. These threads generally do not require large teams or analysis capabilities - simply stating the facts in a clear and concise manner is a key value add.

Voter Intimidation Emails, Real and Fake: EIP identifies intimidation emails sent to supporters of the President threatening violence that saw copycat spread in states where no such letters were received.

Undue amplification of Police Presence: EIP gives an example of undue amplification of police presence at polling places, and suggestions to avoid amplification that dissuades voter turnout.

Inaccurate Voter Registration Claim: EIP debunks a prevalent claim that registered voters exceed the population in some counties.

Out-of-context Video of Election Process: EIP identifies a video of vote counting in a jurisdiction that is taken out of context to insinuate voter fraud, as well as links to the countermessage deployed by the election official in the jurisdiction.

“Hacked” Voter Registration Data: EIP debunks claims of hacked voter registration data, noting the data is public.

False Flag Voter Intimidation Emails: EIP traces through the discourse around the Iranian-attributed voter intimidation emails, noting that trusted information sources must be careful about what is amplified when addressing situations involving violence.

“Friend-of-a-friend” claim: EIP debunks and gives context to a “friend-of-a-friend” claim around poll workers writing on ballots, linking to a counter message by a state board of elections.

Ballot dumping: EIP identifies a ballot dumping counter message that saw significant amplification. Key here was amplification of the local official’s initial counter narrative.

Appendix B: Counter Narrative Best Practices

One of the first and best practices in building credibility is not assuming you have it in the first place. As public security officials, you’re trained to brief straight and narrow. Here’s what we know, here’s what we don’t know, and here’s when we will communicate next.

Addressing misinformation and disinformation doesn’t have to be different. Here are a few points:

State what you can prove (i.e. facts and only facts);

No conjecture and no predicting;

It’s okay to have incomplete information, but you have to state it outright;

Don’t create an information vacuum, in which misinformation can pour in;

Do not give the oxygen of amplification;

Additional Resource: Oxygen of Amplification (Data and Society)

Have thresholds for response.

The last two points are particularly important. Not giving any particular narrative the oxygen of amplification means that you need to be careful to not inadvertently give a falsehood more traction by talking about it in the first place.

In having a threshold for response, you can avoid the oxygen of amplification. You don’t have to address everything but having thresholds for what you will respond to will help systematize and build credibility.

No Response: If a false narrative is reported, but it was one tweet that no other users engaged on (no likes, no retweets), then you addressing it gives it engagement that is unearned and unwarranted.

Context: A risk in responding accepts the premise of the original allegation and gives amplification to it. When we get into a sustained back and forth, those who spread disinformation have already won.

Case by Case: If a narrative is getting some engagement but is particularly egregious or harmful, then respond or if there is a non-immediate public safety consideration.

Considerations: how provably false the claims were, the audience impact of the claims, and the opportunity for affirmative messaging.

Absolute Response: False narratives with high levels of community engagement, media coverage, or immediate public safety considerations.

Appendix C: Content Deep Dives

Of the hundreds of incidents the EIP has analyzed, we have chosen a select few as salient case studies of propagation tactics and dynamics that encapsulate the 2020 mis and disinformation landscape. We have included a few of these studies below, subdivided into the major categories of mis and disinformation narratives observed.

Content that spreads confusion about voting procedures or technical processes

Well Intentioned Misinformation: EIP identifies several instances of well-meaning but misleading content, which typically takes the form of flawed public-service announcements or calls to action. This piece outlines best practices to contain the spread of this kind of content.

Confusion about Absentee Ballot Request Forms sees heavy cross-platform spread: Online confusion that went viral in which voters conflated Trump campaign mailers with government-sent absentee ballot request forms.

Viral Misinformation about Mail-In Ballot Party Affiliation: EIP uses an example video found on Facebook to illustrate a common narrative around mail-in ballots.

Misinformation on California’s VBM Executive Order propagated in Follow-for-Follow Networks: An example of misinformation targeting an expanded vote-by-mail executive order that was propagated by political retweet rings.

Content that may result in direct voter suppression

Amplifying ‘Army for Trump’ Fears: EIP analysts cover the online impact of Trump campaign calls for poll watchers, concluding that both the ‘Army for Trump’ sign-ups and the left-leaning media reaction could contribute to voter fears of violence at the polls and result in voter suppression.

Well-Intentioned Misinformation about Domestic Violence Survivors: EIP analyzed a well-intentioned tweet that claimed that survivors of domestic violence could not vote due to public voter records. EIP worked with the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence to document potential impacts and effective counter narratives.

Analysis of 10/21 Foreign Election Interference Announcement: EIP independently analyzes the recent voter intimidation campaign attributed to Iran, including emails claiming to be from the “Proud Boys” and a video alleging compromised voter data.

Content that may delegitimize the election

Repeat Offenders: Analysis of 43 cases of election-related disinformation that have resurfaced often. Of these cases, more than 50% of all retweets originate from the “original” tweets from only 35 users (out of over 600K users in our dataset). This piece documents how users engaged in reframing and decontextualization to spread misinformation.

Emerging Narratives Around ‘Mail Dumping’ and Election Integrity: How misinformation, sometimes benign, around dumped USPS postage is amplified by political influencers and contributes to delegitimizing the election outcome.

#BallotHarvesting Amplification: This piece is an analysis of a domestic, coordinated elite disinformation campaign targeting election processes by alleging widespread voter fraud. This post explores the timeline of how the ideas in this campaign were initially seeded and then aggressively spread.

Narratives Targeting Electronic Voting Machines: EIP breaks down the past and present misinformation narratives across the political spectrum that have targeted the integrity of electronic voting machines.

A Look Into Viral North Macedonean Content Farms: EIP researchers do a deep-dive analysis of a particular “content farm” that produces right-leaning partisan content, spread through right-wing platforms, designed to draw in domestic partisans and generate revenue.

Delegitimization Meta-Narratives: EIP researchers assess that certain political influencers have been stringing together a series of election-related claims into a broader conspiracy theory, in this case around a so-called “color revolution.” These efforts could serve to ascribe conspiratorial malintent to innocuous future election administration mishaps in order to delegitimize election results.

Ballot Harvesting Narratives: EIP examines a topic that is often used to question election integrity, and has seen considerable attention during this election. Some misinformation reports around ballot collection contained no falsifiable claims and were therefore unactionable under social media platform policies. Others had already received widespread coverage from media outlets. EIP sees this complex topic as a repeated narrative leading up to the election.

Other Case Studies

Foreign vs. Domestic Amplification of Election Disinformation: Using a case of misinformation around purported mail dumping in Sonoma County, CA, EIP researchers trace the impact of domestic vs. foreign disinformation spread, concluding that domestic political actors remain the main spreaders of disinformation.

Uncertainty and Misinformation: What to Expect on Election Night and Days After: Senior EIP researchers describe the state of the information environment for this election season so far, using past trends and current observations to predict the state of the information environment on the last day of voting and afterwards.

“Friend-of-a-Friend” Stories as a Vehicle for Misinformation: EIP outlines a common trope for election misinformation: “friend-of-a-friend” stories. These are social media posts that claim to relay an unsubstantiated but salacious rumor, often encouraging others to copy/paste the story to spread it.

False Voting Claims Spread via Websites and Facebook Ads: EIP analysts trace Facebook ads pushing debunked misinformation, in this case around ballot collection,to a Facebook page and set of websites with ties to Nigeria.

What is the Election Integrity Partnership?

The Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) is a coalition of research entities focused on supporting real-time information exchange between the research community, election officials, government agencies, civil society organizations, and social media platforms. Our objective is to detect and mitigate the impact of attempts to prevent or deter people from voting or to delegitimize election results.

We have been working with the Center for Internet Security (CIS) to observe reports that make it to their misinformation inbox. The EIP conducts thorough analysis on these reports. Most of our work, however, focuses on the real time detection of these incidents. We work with CIS to alert election officials of misinformation incidents when we find them to give election officials a clear picture of network dynamics at play, and offer our help in crafting counter narratives for the targeted electorate.

For more information please visit our website: eipartnership.net, email us at info@eipartnership.net, or follow us on Twitter: twitter.com/2020Partnership.